Vivian. From the 1400-1500 Middle English (derived from the French vitalis, “to live,” and vit, “a life”). Vivian Bearing, as her names suggests, has lived life with drive and nobility, perhaps even a life that has been excessively bearing. Over bearing. She is a formidable, distinguished professor of English Metaphysical poetry renowned for her steely, intimidating rigor. She is a scholar specializing in the Holy Sonnets of John Donne. Now, she is dying. Stage 4 ovarian cancer. “There is no stage 5.” Now, she is research. Once she was the ruthless examiner of literature, of words, of detail down to the weight of a single comma. Now, she is the body under examination. The significance of her life has been reduced to her ability to endure being battered not by the “three-personed God,” but by the impersonal violations of her medical data-gatherers, “Pharisaical Dissemblers [who] feigne devotion.” Once she was willing to sacrifice life for the greater good of greater knowledge. Now, from the factual finality and sterile solitude of her hospital bed, she would gladly trade it all for the comfort and dignity of being known.

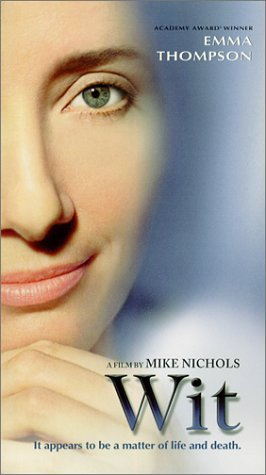

Emma Thompson gives us a gripping and exhausting performance as Professor Bearing. Thompson, in collaboration with director Mike Nichols, adapted Wit from the stage play by Margaret Edson. The stage, or more properly, the hospital bed, belongs to Thompson and her riveting creation of Vivian Bearing. The medical researchers observe Professor Bearing’s body being devoured by cancer with detached interest and professional delight. We the audience can only watch helplessly. The cancer, as is the subject of Donne’s sonnets Bearing observes clinically, “appears to be a matter of life and death.” But as the reality of her condition becomes increasingly person, Bearing begins to look at herself and her life differently:

This is my play’s last scene; here heavens appoint

My pilgrimage’s last mile; and my race

Idly, yet quickly run Hath this last pace

My span’s last inch, my minute’s last point

And gluttonous death will instantly unjoint

My body and soul….

John Donne… I’ve always particularly liked that poem. In the abstract. Now I find the image of my minute’s last point, a little too, shall we say… pointed. I don’t mean to complain but I am becoming very sick. Very sick. Ultimately sick, as it were. In everything I have done, I have been steadfast. Resolute. Some would say in the extreme. Now, as you can see, I am distinguishing myself in illness.

The film is entitled, “Wit.” Wit refers to a quality of metaphysical poetry, and (in that sense) the title is itself a bit of metaphysical poetic wit. Samuel Johnson describes this sort of wit as “dissimilar images… yoked by violence together” so that the reader is startled out of complacency and forced to think through the argument of the poem. A literary dictionary explains that the use of wit “reveal[s] a play of intellect, often resulting in puns, paradoxes, and humorous comparisons.” John Donne was considered the master of wit. Does he not draw out a wry smile when he prays to God as slave-master and liberator: “Take me to you, imprison me, for I Except you enthrall me, never shall be free.”

Vivian Bearing is now herself a violent collision of life and death, of knowledge and life, of ideal and reality, of student and teacher, of scholarship and love. Donne brings his poetic images together to offer us insight, understanding, and meaning. Wit allows us to observe a scholar, who knows Donne’s poetry exhaustively, “unjointed” by the collision of life and death. The question beneath her struggle is whether what she knows so well (Donne’s sonnets) will bring her understanding and rest. Is there a way to live and die with wit?

As you prepare to watch and discuss this film, take some time to consider Donne’s most famous Holy Sonnet, “Death Be Not Proud”

Death be not proud, though some have called thee

Mighty and dreadfull, for, thou art not so,

For, those, whom thou think’st, thou dost overthrow,

Die not, poore death, nor yet canst thou kill me.

From rest and sleepe, which but thy pictures bee,

Much pleasure, then from thee, much more must flow,

And soonest our best men with thee doe goe,

Rest of their bones, and soules deliverie.

Thou art slave to Fate, Chance, kings, and desperate men,

And dost with poyson, warre, and sicknesse dwell,

And poppie, or charmes can make us sleepe as well,

And better then thy stroake; why swell’st thou then;

One short sleepe past, wee wake eternally,

And death shall be no more; death, thou shalt die.

-Steve Froehlich