The faded family banner still flies atop the peak of the majestic Victorian homestead in which the family Tenenbaum grew up. Well, no. That’s not entirely correct. They never really grew up, and that’s the problem. Each member of the family realized notoriety, even fame and glimpses of glory. But this is no family, and they resemble no family among our acquaintances. They live lives cluttered by the elaborate ornamentation of isolated, self-centered existence. They fit themselves within the borders of a family portrait, yet the only thing they share is a mutual loathing of the family patriarch, Royal Tenenbaum. Yet, as we look into the stylized and eccentric lives of these sad, quirky, and silly people, we recognize a humanness that is common, a plight so ordinary we might miss it were it not drawn large for us upon the creative canvas of Wes Anderson.

This is the 3rd major film from Wes Anderson. The Royal Tenenbaums (2001) follows Bottle Rocket (1996) and Rushmore (1998), both offbeat comedies that focus on precious young people who find themselves out of place in the world, who discover that the world is not ready for their genius. The Royal Tenenbaums was co-written by Anderson’s long-time friend, Owen Wilson, who also appears in the film as the Eli Cash. Cash is the life-long friend and neighbor of the Tenenbaum children–he’s a successful author of western-style fiction even though his talent is panned by the literary critics.

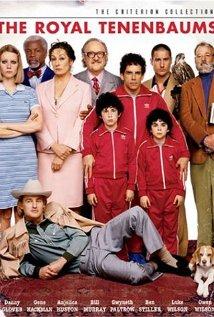

The father of the Tenenbaum family is Royal (Gene Hackman), the smirking, irresponsible, arrogant father who has not lived with or communicated with the family for many years. When we meet him, he is being evicted from the hotel in which he has been living–his credit has run out. The Tenenbaum matriarch is Etheline (Angelica Houston), once celebrated author of a book on parenting child prodigies–all 3 of the Tenebaum children were hailed as geniuses. She now works for the museum and plays contract bridge. The 3 children are Chas (Ben Stiller), Margot (Gwyneth Paltrow), and Richie (Luke Wilson)–they are all neurotic. Chas, the business whiz kid, made his fortune in real estate before he entered high school. He is now a widower, and the paranoid parent of 2 boys. Unable to cope with his fears, he moves back into the family house. Margot wrote a $50,000 prize-winning play when she was in the 9th grade, but locks herself away in the bathroom, alone with her secrets. She decides to move back into the family house. Richie, a world-class tennis player, suffered a meltdown at the finals of the US Open–since then, he’s been traveling the world on cargo ships, until he is summoned home by the news that Royal delivers to Etheline, “I’m dying of stomach cancer.”

He’s not, of course. Royal is lying again. He’s broke, and needs a place to stay. He’s alone and has no one to be the butt of his sarcasm. Nevertheless, the family is reunited, and therein is the question posed: Can these angry, wounded people be friends? Is it possible for them to be a family? As Royal says, “I want my family back.”

There is no doubt in anyone’s mind that he does not deserve to get his family back, and that he is the root cause of the family’s dissolution and excessive dysfunction. He swindled Chas. Margot, not a Tenenbaum by birth, is always introduced by him as “my adopted daughter.” When he talks to his grandsons about their mother, he says, “I’m very sorry for your loss. Your mother was a terribly attractive woman.” Yet, even as we are convinced that Royal has been a terrible father and husband, that he has not yet experienced that deep transformation that will re-orient his attitudes and perspective, we know that he wants the right thing. We find ourselves pulling for him, hoping that somehow, some way, these individuals will find one another and learn how to love one another. There is a strong sympathy holding this story together, an urgency that breathes with frequent smiles and occasional outright laughter.

Anderson presents these characters to us–in a way, he shoves them in our face, and we see them as individuals, and we see through them. They each have their own room in the big house, rooms that are so different that each is like a private universe. They tell us their own private stories disconnected from those closest to them. They have all broken away from the home, have all been driven away from the home before the story begins. But now to find themselves they must pick up the threads back at the place where they were broken. As an ironic foil, Eli Cash, an outsider, wants the fame of the family and the talent that his friends possess. Consequently, his life has been spent trying to get into the family just as vigorously as the children have been trying to get out. He wants those impersonal superficial things that have driven the family apart. In the end, he gets what his friends are willing to give him: love.

Is redemption, reconciliation, and forgiveness possible? Royal stumbles forward in his own misguided way. As you watch this process unfold, watch how Royal begins to take his children out of the surreal existence under the roof of the old house and out into the real world. Observe how death plays a central role in the process of change. Each one of the characters must face death. In each character’s life, something must die. Anderson gives us some delightful and funny images that tease out the death theme. But don’t let the humor distract you from the important role it plays in the larger message of redemption. The uncomfortable sexual tension between Richie and Margot makes us feel how confused this family is about understanding, experiencing, and expressing love.

The cast is marvelous with crisp, thoughtful, nuanced performances by each one. Hackman is brilliant. The script and dialogue are understated so that the humor is wry not slapstick. The film is stylized – the episodes framed like portraits conveying the detached impersonal world of the characters. Each portrait is filled with the fascinating details that tell us something about the room occupied by each character. The clothes worn by the characters are like costumes or symbols. The tone of the film is gentle and sympathetic–it does not mock these characters for their troubles and their foibles, but it understands them. So will we if we listen, because these are people like us, people in need of grace, redemption, and healing. We are people who need to come home to find that for which our hearts have been longing.

-Steve Froehlich

Questions for discussion:

- Why is the film titled, The Royal Tenenbaums?

- Why have the characters left the homestead? From what are they running, or what are they unwilling to face?

- How are the images and how is the theme of death used to advance the theme of healing, forgiveness, and reconciliation?

- How does the family home function as a metaphor for the lives of the people who live in that house?

- What role does risk-taking play in the commentary of the story and in the transformation of the characters?

- What significance do you place on the opening and closing image of Mordecai?

- How does our discomfort at the sexual tension between Richie and Margot help us understand the film’s depiction of how love is recognized and expressed? Comment on the different ways Richie shows love to Royal, Margot, and Eli, as well as the other characters’ reaction to that demonstration.

- Why is it meaningful for Richie to put the boar’s head back on the wall? (Note that the wall still has the marks of where it once hung, and remember the scene in which the boar’s head is discovered.)

- How does Royal change, and how does his change influence the members of the family?

- Is there forgiveness and healing? Is it experienced uniformly among the family? If it is experienced at all, is it warranted?

- To what Bible passage or story does your reflection on this film take you? Why?