It sounds much too bland to ask: How would you live today if you knew that it were your last? For someone who really did care about squeezing every drop of living out of life, the proposition must be framed with much more imagination. For instance, Is the joy of watching the poor bus driver go into a wild-eyed panic because you have stepped out in front of his oncoming bus a fair exchange for the very real possibility of have having your ticket permanently punched a few days early? Frantisek Hána (Fanda) would have to give it serious consideration. It would be quite a show, one worth seeing. If he took that step off the curb, you can be sure he would stand facing the mayhem bearing down upon him with a bemused calm that would allow him to absorb the full effect of his mischief.

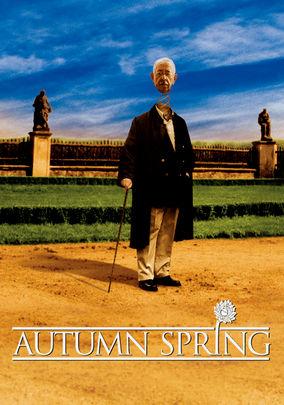

Autumn-Spring is a gem of Czeck cinema featuring the acclaimed veteran duo of Vlastimil Brodsk and Stella Zázvorková as Fanda and Emílie, roles for which they were awarded the Czeck Lion. The married couple is in their autumn years. Emílie insists on using their time and resources for the practical necessities of preparing for the inevitable so that they are not a burden on anyone else. Fanda, however, is stoical about such mundane matters—his imagination and playfulness are alive even inside his aging body and he will have nothing to do with living practically and “going quietly into that good night.” He and his all-too-willing accomplice, Eda, are busy scheming up their shenanigans: posing as subway agents so they can steal kisses from pretty passengers who don’t have the proper fair, posing as a retired opera conductor and assistant while allowing greedy real estate agents wine them and dine them in hopes of a lucrative sale.

This is a film touched by the Eastern European pessimism or sadness that comes from nearly a century lived in oppression. The actors themselves have weathered their homeland’s bleak hours, so their performances function as a somewhat unintentional testimonial to people who have waited to die well. The film assumes that death is inevitable—that much is not in debate. But it does ask us how we will live, regardless of our age, as people who are dying.

Fanda doesn’t really want to cheat death—he simply does not want to give up on the joy of life a moment too soon. However, his determined refusal to be practical exposes a deep root of selfishness and self-centeredness. His own thrill-seeking and joy-riding eventually reveal how unwilling he has been to be loving toward others, especially his loyal and persevering wife.

Autumn-Spring shows us Fanda and Emílie having grown old together, but it is not essentially a film about old age or death, although death is always present. In a much more charming and often amusing manner it echoes the line from William Wallace in Braveheart: “Every man dies, but not every man really lives.” It reminds us of the power which humor, imagination, and joy have to literally sustain our lives. It asks us to think about the relationship that love and personal happiness have to one another.

Director Vladimír Michálek gives us a simple unadorned film so that the characters come alive with depth and dimension. Yet, the simplicity functions as a powerful reminder that great joy in life does not come from those distractions that often complicate our lives. Childlike Fanda uses only his imagination to make a playground out of a world which knows little of the adult gadgets and toys that keep us busy and distracted, weary in our drivenness.

The film’s subtitles are well-translated and capture much of the nuance expressed in the story and in the rich facial expressions of the characters. One of the great ironies of this hopeful and affirming film is that it marks the end of the life and career of Vlastimil Brodsk—he committed suicide shortly after the film was completed.

-Steve Froehlich

Questions for discussion:

- How does the film’s simplicity complement the theme of happiness?

- Why do you think Fanda is so indifferent to Emílie?

- Why do you think Emílie is so angry with Fanda?

- What is the source of the undercurrent of cynicism in the film?

- How and why do Fanda and Emílie change, if in fact you think they do?

- How does the film enlist your sympathies for the characters? Do your sympathies change? Why?

- Do you think the film is hopeful? Why, or why not?

- How does the film explore the tension between possibility and necessity? Between truth and happiness?