Author: Steve Froehlich

Crimes and Misdemeanors

General

General Movie Review

Movie Review

Woody Allen (writer and director of Crimes and Misdemeanors), notorious for doing some things badly, does at least two things well: he asks good questions, and he creates interesting characters to ask those questions.

Much of Allen’s work is painfully autobiographical. The questions he asks appear to be his own, and he himself is one of the characters of his creation. So his own neuroses and quirks fill the story and the screen. But underneath the tragi-comic idiosyncrasies, he’s really not such an odd duck.

Crimes and Misdemeanors plays on some of Allen’s favorite themes: the unfairness of life, frustrated desire, unfulfilled ambition, conflicted conscience, honesty, mediocrity, and humorous ironies that spin out of human imperfections and flawed choices.

Allen effectively weaves together a cast of complex characters made up of Martin Landau, Angelica Huston, Sam Watterson, Mia Farrow, Claire Bloom, Alan Alda, and of course, himself, all of whom give very fine performances. Crimes and Misdemeanors plays like a thriller, like a classic film noire. But its darkness emanates not from ominous people and situations, but from the human heart.

Yet Allen gives us something different in this film. His style of realism gives each of us watching the story unfold full knowledge of the situations, and thereby invites us to ask the questions with the characters as each situation develops. Exactly how selfish are we? How far would we go to protect our happiness and reputation? Is our comfort worth another person’s life?

Perhaps the biggest surprise of all is that Allen offers answers to the questions he raises.

-Steve Froehlich

The Decalogue

General

General Movie Review

Movie Review

Ten Commandments. Ten Films.

One work of art. One masterpiece.

The Decalogue is a masterpiece of film-making written and directed by the Polish film genius, Krzysztof Kieslowski. I know, you’re thinking, All the Chesterton House Movie Night films are great. But, truly (verily, verily) all the critics agree – every one of the 30 whose review of The Decologue I read agree: The Decalogue is magnificent cinema.

You remember the Ten Commandents, surely. We can recite them in classic King James prose:

Thou shalt have no other gods before me.

Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image.

Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord thy God in vain.

Remember the sabbath day, to keep it holy.

Honour thy father and thy mother.

Thou shalt not kill.

Thou shalt not commit adultery.

Thou shalt not steal.

Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbour.

Thou shalt not covet.

So, 1 film about each commandment? Not exactly. Kieslowski gives us 10 stories that play with what it means to keep or understand the Commandments. All 10 stories take place in the same Warsaw apartment complex, and we see characters from the different stories passing through in the background. Kieslowski gives us a universe in which the lives of men and women, boys and girls, are intertwined in their common struggle. Keeping or breaking the Laws of God impacts the way they (and we) live together. But how are we helped by keeping God’s Laws? How are we hurt by breaking them? Is it as easy to keep these Laws as it is to quote them? Does keeping them bring understanding to the struggle of life? Does breaking them bring freedom and joy in the escape of God’s tyranny? And who can break only one at a time – if we steal are we not also coveting, if we murder are we not also taking to ourselves another god?

We will watch 2 of the 10 films this Friday night. Each film is about 1 hour in length. The series was initially produced for Polish television, so each segments fits the television time format… more or less. Then we will discuss what Kieslowski has presented to us in his amazing creation, The Decalogue.

-Steve Froehlich

Dr. Strangelove

General

General Movie Review

Movie Review

“Dimitri, we have a little problem.” That’s the President of the United States talking to the Soviet Premiere.

“He went and did a funny thing, Dimitri.” That’s the President explaining to the Premiere that General Jack D. Ripper has launched a nuclear strike because he’s convinced that the Commies are poisoning “the purity and essence of our natural fluids” by adding fluoride to the water supply.

“I think I’d like to hold off judgment on a thing like that, sir, until all the facts are in… I don’t think it’s quite fair to condemn the whole program because of a single slip up, sir.” That’s General Buck Turgidson, head of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, urging the President not to condemn the nuclear defense system simply because they had not foreseen the possibility of Gen’l Ripper unilaterally initiating Armageddon.

Dr. Stranglove is Stanley Kubrick’s breakthrough comedy about the plausible absurdity of nuclear deterrence, a Cold War satire showing machines at the mercy of lunatic generals. The influence and role of technology is a theme to which Kubrick returns in his other masterpiece, 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Dr. Strangelove is consistently heralded as one of the great films of the 20th century. It features brilliant performances by Peter Sellers, George C. Scott, Peter Sellers, Slim Pickens, Peter Sellers, and the debut film role of James Earl Jones. (Did I mention PeterSellers? Sellers plays three roles.)

As we face a culture even more densely saturated by technology, Dr. Strangelove remains “remarkably fresh and undated – a clear-eyed, irreverent and dangerous satire” (so says Roger Ebert). Dr. Strangelove: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.

Frankenstein

General

General Movie Review

Movie Review

It was a dark and stormy night. Really. It was the summer of 1816 on the shores of Lake Geneva in Switzerland, a site previously visited by literary giants like Milton, Rousseau, and Voltaire and a retreat to which another generation of literary greats had gathered for what some have called the most famous house party in literary history. Among the friends were Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and Mary Shelley (Percy’s wife). In response to a mutual dare to write a ghost story, Mary Shelley wrote the legendary novel, Frankenstein (published 1818). She was only 19.

The novel was an immediate success. Ironically, almost anticipating the transformation that the story would undergo in the 20th century, the first dramatic production of the tale, Presumption, was produced on stage in 1823 and the first parody version was produced in 1825 as Frank and Steam. In 1910, it was first adapted for the screen in a silent short produced by Thomas Edison.

The most famous film version of Frankenstein is, of course, James Whale’s 1931 production, which made Boris Karloff an international star and gave the viewing public an imposing image that cast a shadow across the 20th century. The meticulous craftsmanship of the film’s composition and storytelling launched the career of Whale as a major director. The classic film is important in the chronology of visual arts — City Lights, the Charlie Chaplin silent masterpiece, was released the same year, and the sound effects incorporated into the film created an audio revolution. The visual effects of the film were the creation of makeup master, Jack Pierce. Pierce explained that he “built an artificial square-shaped skull, like that of a man whose brain had been taken from the head of another man.” He fixed wire clamps over Karloff’s lips, painted his face blue-green, which photographed a corpse-like grey, and glued two electrodes to Karloff’s neck. The wax on his eyelids was Karloff’s idea. “We found the eyes were too bright, seemed too understanding, where dumb bewilderment was so essential. So I waxed my eyes to make them heavy, half-seeing”, Karloff explained. The entire monster’s costume weighed over 40 pounds.

“It was on a dreary night in November.” So begins chapter 4 of the novel, and this marks the starting point for most of the film adaptations of the story. With the exception of the 1994 film by Kenneth Branagh, all the Frankenstein movies focus on the creation of the monster rather than the reflections of the creator on what he has done as he faces the consequences resulting from his creation. However, even as the film sensationalizes the horror of a creature, assembled from body parts robbed from graves, animated by the raw power of natural energy harnessed by the cleverness of scientific machinery, a central theme from the novel cannot entirely be masked.

Shelley deliberately parallels Victor Frankenstein as creator with God as Creator. As we watch the creature jolted to reanimated life, we ask not only: Is this possible? but: Should this be done? Frankenstein offers these words of warning in the novel: Learn from me, if not by my precepts, at least by my example, how dangerous is the acquirement of knowledge, and how much happier that man who believes his native town to be the world, than he who aspires to become greater than his nature will allow.”

Frankenstein is indeed a myth for modern times. The science hinted at in the novel and caricatured in the film seems to be a looming possibility in our present generation. Certainly the ethical questions are still with us: To what end should scientific knowledge be used? The film depicts the all-too-common reality that our good intentions in justifying our bold and reckless use of power and knowledge often go awry, resulting not in the good we had anticipated but the evil that we feared.

The story inescapably poses another question: Is the monster human? Each of the several Frankenstein films struggle with the degree of humanness and subsequent empathy that a humanized monster would evoke. What is the source of his evil? It’s interesting to note that the novel and the film deal with these questions quite differently. Shelley’s Romantic ideals frame the monster’s evil as the result of his cruel treatment (not his nature, but his nurture) — even though hideous externally, he could have been good if he had been treated with compassion. The film versions, however, make the monster intrinsically evil — he is corrupt because his very parts are corrupt, and as an irredeemable beast he can only be destroyed.

Frankenstein’s creation is nameless. But the corruption and evil that we face in our real lives is not nameless. Perhaps one of the questions that the movie invites us to ask is: What name will we give to the things of life, even the things of our own creation, that have gone horribly wrong? Those things that we have attempted with noble and sincere aspiration, but in the end are not what we had hoped they would be? Dare we ask: Who is the monster?

-Steve Froehlich

Fight Club

General

General Movie Review

Movie Review

“Things that you own wind up owning you,” says Tyler Durden, provocateur, bare-fisted brawler, soap salesman. “Martha Stewart is polishing the brass on the Titanic.”

“Shocking, disturbing, possibly dangerous, visceral, hard-edged” write reviewers of this intelligent and jarring film by David Fincher (The Game, Seven, Alien 3). Fincher, in a truthful and witty screenplay, tells us that he is giving us front row seats for the theatre of mass destruction. The fight, the deep soul struggle to break free from the modern mania of consumerism and the cult of New Age sensitivity wages between Durden (Brad Pitt) and the nameless narrator (Edward Norton) who goes by “Jack” as he wanders like a tourist from one self-help and recovery group to another. “Our great war is a spiritual war, our Great Depression is our lives,” preaches Durden.

“We’re all raised by television to believe that one day, we’re all going to millionaires, movie gods and rock stars, but we won’t And we’re figuring that out now.”

“Your father was your model for God. And if your father bails out, what does that tell you about God?

“You are not your job. You are not how much you have in the bank. You are not your khakis.”

Jack works for a large auto parts company and he spends his days calculating the value of human life – how many law suits and how much loss of profit the company can sustain before recalling its defective parts. As Jack ponders the value of his own life and his own addiction to recovery, he concludes that he will be valuable to someone else only when and if he’s terminally ill. Then he meets Tyler Durden, a Kafka-esque alter ego. They fight, pound their bodies to bloody exhaustion, and discover a rejuvenating sense of life. This spiritual awakening leads them to form Fight Club. They discover that men everywhere want to join, to fight, to rage against being emasculated and isolated. But, as one reviewer observes, “these guys are beyond angry. They are heartbroken and lost.” They are searching for the souls that slowly and secretly have been stolen from them.

Fight Club is a visual spectacle. Not everyone will like the way it tells the story and describes the way men (and women) are desperate to escape the dehumanizing trap of modern materialism. Susan Faludi is a feminist who offers a thoughtful assessment of the impact of the radical feminist movement upon men. Her recent book, Stiffed, is about the need men have to regain and be restored to a healthy masculinity and male identity. Her thesis points to the tension of this film – individual human life really does have worth after all. It’s worth the struggle to tear down all the icons of our age that makes us slaves, sub-human, isolated. Ironically, Durden’s charismatic and violent liberation itself becomes a new tyranny, which Jack comes to realize as the film moves into its final act.

Edward Norton, Brad Pitt, and Helen Bonham Carter all give superior performances. The film dares to evoke images of Columbine to explore some profound reasons that drive young men to do these things. In the midst of such great technological wizardry and electronic intimacy, why are we alone, why are we angry, what weight is pressing upon us to fill us with rage, and how do we discover freedom and belonging.

The normally austere BBC reviewer writes, “Fight Club appears threatening to some because it seems to challenge the safety of the modern world. All you really need to know is that Fight Club rocks!”

-Steve Froehlich

Gattaca

General

General Movie Review

Movie Review

Set in the “not too distant future” Gattaca asks questions essential to defining the identity, value, and purpose of human life. Vincent Freeman is a “faith-child” (born the old-fashioned way) living among the elite superstars of genetic engineering. Yet Vincent is determined to realize his dream of doing what is reserved for the privileged and selected few – he wants to be a navigator on a rocket launch to Titan, one of the moons of Saturn. But to do this, he must borrow the identity of another.

What gives us dignity as people?

When are you good enough to make a difference?

What is perfection?

Who am I trying to please and whose approval matters most?

The subject of eugenics, genetic manipulation, selective breeding, and utopian idealism is hardly new. With the birth of Dolly, few doubt that a human clone is far behind if not here already. Crude attempts at human engineering have not been limited to Nazi Germany. Recently 30 US states publicly apologized for their role in the eugenics movement in this country and the incalculable human damage done in the name of eugenics. The government admitted to the forced sterilization of 8,000 mostly poor, uneducated men and women in an attempt to eradicate hereditary “defects” and chronic social problems such as poverty, immorality, crime, addiction and ignorance. Ah, what price we are willing to exact upon others so that we may enjoy life as we think it should be. What immeasurable corruption lies within the hearts of those who want life and people to be “just right.” With a subtle and quiet power, Gattaca shows us a world that is not too unlike our own, the world our world might easily become.

Gattaca is an elegant, stylish, and thoughtful sci-fi thriller. The lead roles are well acted by Ethan Hawke, Uma Thurman, and Jude Law. The story works as a classic triumph of the human spirit (“there is no gene for the human spirit”), as well as a murder who-dunnit and a sci-fi morality tale. Director Andew Niccol’s debut creates a stunning panorama in which he tells a superb story that is filled with simple profound questions that haunt the soul and invite us both to look within and to the heavens above.

-Steve Froehlich

Hard Day’s Night

General

General Movie Review

Movie Review

John is gone. George is gone. Paul is now Sir Paul. Ringo is… Where is Ringo anyway?

2004 marks the passing of 4 decades since Richard Lester (director) and “the boys” gave us A Hard Day’s Night. For the Beatles the release of the film in September 1964 framed a sensational year that began with their first appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show on February 9, an event witnessed by an unprecedented 70 million television viewers.

From the moment the images of A Hard Day’s Night first hit the screen, the film has occupied a prominent and important place in American cultural iconography. Many have suggested that the extraordinary impact of the film was helped by the timing of the British musical invasion – The Beatles made their prime-time television debut just 3 months after the assassination of President John F Kennedy, and the film burst to life on American movie theatre screens only days in advance of the first anniversary of Kennedy’s death.

A Hard Day’s Night is recognized as an important film because of the role it played in film-making. It is not remembered for its masterful scriptwriting, although it has lots of Pythonesque quips and repartee that impishly make their way into witty conversation. It’s not renowned for its character development – The Beatles are the characters playing themselves, and it’s the film’s job to get out of the way so we can see them. The film is the first rock video in which the film serves the music and the performers (quite unlike the Elvis, Frankie, and Annette films that required some sort of story, no matter how thin, to create an excuse to introduce the music).

In ways somewhat similar to post-war theatre that was breaking down the conventions of formal staging – pressing through the proscenium, coming face-to-face with the audience, dragging the audience into the experience, shamelessly propagandizing – the film broke free from the waning generation of movies featuring rock ‘n roll stars like Elvis Presley. But Elvis’ bad boy image existed within tightly scripted romantic storytelling. A Hard Day’s Night introduced a new level of realism in the tone of movie story-telling and in the relationship of the screen personality and the audience. The film feels like a home movie with the kids mugging for the camera knowing that they are on film and that the audience is watching them. The film is not a mockumentary a la Christopher Guest’s A Mighty Wind and Best in Show – it is an uninhibited invitation to enter the life of the Beatles for a day and play, and with all the playfulness aside it is an attempt to make us feel like we have really gotten to know “the boys.”

Lester, while not the inventor, was a big-screen innovator of the hand-held camera. The camera movements led to a fast-paced quick-cutting editing style that deconstructed the video line of the movie – he gave us quick hits and sound bites in a realistic setting that suggested a new speed of life. Life is fast, energetic, sudden, emotionally charged, orgasmic. Life is exhilarating, but exhausting. Life is buoyant, but smothering. What do I do when I need to escape, get away, find myself? Yet, I am unwilling to completely detach myself from the energy of the crowd.

There is in A Hard Day’s Night a seamless and perhaps unconscious weaving together of technology and life. We see lives in which media, images, and information are beginning to blend together in ways that today we recognize as normal, but was quite new at that time. It seems to be an admission or a realization that we had become a media culture. It was a kind of techno-confession that we in fact do… and in fact want to look at the world through an artificial lens… perhaps because we find that view more interesting, or more palatable. Perhaps we wanted to hide; perhaps we were hoping to find a better world; perhaps because the world as we were coming to know it was too much to bear.

We will never see “the boys” more innocent than they appear in this film. We will never see the movement which this film inaugurates more idealistic and joyful.

But we still have the music.

-Steve Froehlich

Minority Report

General

General Movie Review

Movie Review

“You’d think we’d have found a cure for the common cold by now,” opines Director Burgess as he blows his nose. In the year 2054, there may be no cure for the flu, but the Bureau of Pre-Crime claims that they have found a cure for murder. The Washington DC that we know as a madhouse of murder has been transformed by the mid-21st century–murder has become a thing of the past thanks to the new police system that prevents the crime before it happens.

“Minority Report” is director Stephen Spielberg’s stylish techno-thriller based on the science fiction short story by Philip Dick. “Blade Runner” and “Total Recall” were also inspired by Dick stories, and “Minority Report” is repeatedly compared with “Blade Runner” as a visionary, provocative sci-fi cinema.

Science fiction of every literary form focuses on social and political rebellion and transformation. Something needs to change. However, living in the present we cannot see clearly because we are too familiar with life as it surrounds us. So, science fiction prophets change the setting to a world in which both our hopes and our nightmares have become a reality. “Minority Report” takes us forward only half a century from the present, and the changes to life-as-we-know-it are not outside the universe of what we can conceive might be possible (okÉ the elevator cars might be an exception). So, while philosophical in tone and futuristic in style, “Minority Report” maintains a sense of the present as it explores the ideas that shape the story. Therein lies much of its power–we can’t write if off as something that could never happen.

In the film Washington DC has become the safest city in the U.S. because the Department of Pre-Crime has found a way to prevent murder before it happens. Three children, specially gifted with pre-cognition, are able to see murder before it happens. They are literally the brain-center of the Department of Pre-Crime–they exist in a semi-comatose state in a bath of fluids. The images that appear in their brains are wired to computer screens monitored by the Pre-Crime police–they see the crime-to-be-committed, and the police run to the scene of the would-be crime to arrest the criminal before the commission of the act. So, the images and ideas of the film set up several serious questions.

In the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks in New York City, what price are we willing to pay to feel safe? The motto of the Pre-Crime unit is: “That which keeps us safe also keeps us free.” We are living in a changed world after 9/11, and many people live with heightened fear and anxiety. Many of us have envisioned draconian security measures that have become necessary for us to continue to feel secure in our homes.

Serious crimes require society to take serious action. Who hasn’t wished that someone could have intervened in time to prevent the senseless taking of life? If hindsight is 20/20, wouldn’t it be great to have that knowledge in advanceÉ assuming, of course, that we would put that information to honorable use. What is more honorable than saving lives?

Our pursuit of justice is many times energized by the evil we have experienced. So it is with John Anderton (Tom Cruise), chief of Pre-Crime. His little boy was kidnapped, right under his nose, 6 years ago, and he is haunted by what he could have done to prevent that crime from occurring. He is determined to do whatever is necessary to make sure that a crime like that never happens again–that no parent ever endures his pain. What could be more universal that the desire to shield one another from suffering and harm?

The film raises questions about personal safety, fear, justice, protection, power, checks and balances, criminal prosecution, government, privacy, and the sanctity of life. Like most science fiction, “Minority Report” does not answer all the questions it raises, but it does manage to fix a glitch in the system.

There is a cool, clinical mood to much of the film. Cinematographer Janusz Kaminski (“Schindler’s List”) paints the screen in sleek, steely blue. The tone is indifferent and detached (yet, the chrome-like scheme suggests speed, suddenness, steely-swift justice) pointing to the depersonalizing consequences of the technological advances being championed. The Pre-Cogs do not give their gifts for the good of their neighbors, but their brains are used thanklessly–they are little more than machines. Individuals lose their identity to the scanners and optical readers that monitor their movements–their names are shouted out by digital billboards (designed to make advertising personal), their movements are tracked (because if we want to be protected we have to be found when we need help). As we watch this future world, we find that all the technology makes sense–we can see ourselves wanting it in our lives for the same reasons the characters in the film probably welcomed it into theirs.

But is it too late to undo the madness?

“Minority Report” is about seeing. Stylistically it employs a vision of the future. But it also acknowledges an increasingly prevalent view of the world, and our view of our place in the world. To undo the tyranny, Anderton has to get new eyes, literally. He is blind to the immorality of Pre-Crime and the abuse of the Pre-Cogs. He has to stop his addiction to the drug “Clarity” that keeps him reliving the past. He has to interpret what the Pre-Cogs “see” when they predict that he will murder a man he does not know in 36 hours. He is a man known for integrity, and he thinks of himself as one who would never behave any other way–so he has to explore his own self, his motives, and “see” himself in a new way.

“In the country of the blind, the one-eyed man is king.”

In a way quite similar to “Brazil” and “Twelve Monkeys,” “Minority Report” is about control. Ironically, the savior figure is Agatha, one of the Pre-Cogs. Yet she is helpless. Her body is limp and weak, barely able to stand. There is an extraordinary cinemagraphic moment when Anderton is holding her–her head on his shoulder is looking back, he is looking forward, and their eyes tell all. Anderton believes that the Pre-Crime Department has found a way to control the evil of the human heart, but he discovers that even the Pre-Crime developers are corrupt. He set his eyes to look in another direction.

Finally, the film toys with some religious ideas and images. Perhaps most prominently it ponders the tension between predestination and free will, or fatalism and determinism. Can we change the future? Are we doomed to do what has been foreseen? If we cannot choose (and Agatha pleads with Anderton as he points his gun at the man the Pre-Cogs saw him kill, “You can choose!”), how are we not machines, and why should we not employ sophisticated technology simply to manage our existence? Michael Karounos writing in the “Journal of Religion and Film” observes: “The area where the Pre-Cogs are kept is referred to as ‘The Temple’; the police officers are called ‘priests’ and ‘clergy’; the punishment chamber for the future murderers is called a kind of ‘hell’; and the ‘handcuffs’ are an immobilizing headset which is referred to as a ‘halo.’ Moreover, there are three Pre-Cogs (constituting a kind of trinity) and the warden of the ‘death penalty’ wing is called Gideon.”

In “Signs” the wife of Graham Hess tells him with her dying breath, “See!” Open your eyes – stop walking around in a blind stupor. “Minority Report” asks us to see, too. Are we blind? Are we controlled by fear? Are we moral beings that have responsibility for the choices we make? Are we willing to change the way we see the world and embrace solutions to the problems that plague our cities and invade our lives?

“Minority Report” is brilliant visually with solid performances by Tom Cruise, Colin Ferrill, and Max von Sydow. Samantha Morton is mesmerizing as Agatha. It’s a long film–2 hours and 20 minutes. We will start the film on time so we will have some time for discussion afterwards.

-Steve Froehlich

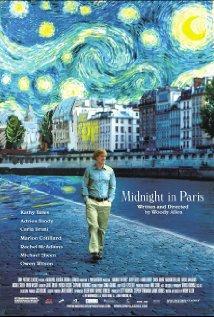

Midnight in Paris

General

General Movie Review

Movie Review

As Roger Ebert says, “There is nothing not to like about this film.” Indeed. From my first viewing, I was thoroughly charmed.

Midnight in Paris (2011) is a pleasant potpourri of literary devices: love, longing, Paris, famous people, and a bit of time travel. Of course, since it’s a Woody Allen film, in some way you can be sure it is about him – don’t all of his films have an autobiographical narcissism? But in this case, it’s easy to look past his doleful eyes and enjoy the film. Owen Wilson (Gil) and Rachel McAdams (Inez) as the leads are pitched just right, and the contrast set up among the other principals is structurally compelling and satisfying. Kathy Bates, Adrian Brody, and others have delightful cameo roles. The time travel device works (besides, it’s Paris and it’s supposed to be a magical city, right?). The story is thoughtful enough and sweetened by some deft brushes of romance. Visually it is artful and alluring – the visual style is part of the idea of the film, and art (something of a composite character) has a voice in the story.

The myth of the golden era. Many of us live in the grip of nostalgia, the desire for something different, the illusion of something better, a sour discontentment. The grass is always greener…. Gil is a screen writer by day who has written a novel. The literature of television is fleeting to him, something so insubstantial it can be switched off. But the world of the novel is enduring and significant in part because it is tied to the past. The problem is that the screen writing pays the bills• the bills Inez is racking up by all her indulgent spending. She cannot imagine that Gil would want something more than what he has, and consequently offers him no encouragement. So, the search for guidance and illumination plays out in the classic city of the arts, Paris. Here, Gil has to find his way. Settling for the way things are in the present, while practical, is a decidedly unfulfilling prospect. Reaching for his ideal is a risk that will require him to let go of some of the security of the present. Gil’s courage to “go for it” is energized by nostalgia, the subject of his novel. He looks back romantically at the icons of a golden era who dared to do what he longs to do. But as he does so he realizes that he can be seduced by romantically idealizing the past, or he can learn from the past, an act that will require humility.

These are important questions for us as Christians. With what perspective do we pursue our life goals? Many of us are trapped by many forms of idealism. Gil looks to the past for salvation even as we do. The historical reality of the Cross, Resurrection, and Ascension are the foundation for all the historical ground which follows. That ground beneath our feet gives us joy and hope. In Christ, the long arm of the past defines the present and persuades us that even in spite of sin the work of Creation continues so that by grace humans can flourish. We can have dreams, and they are worth pursuing.

Woody Allen would say, I think, that Gil is saved by art. We would say, by the Artist. But the role of art, the grace of the Artist, is no less profound for us. The present and the future for us have little significance unless we value the past and humbly learn from it.

-Steve Froehlich