Watching any of the films by Krzysztof Kieslowski is like meditating upon an impressionist painting by Renoir or being embraced by a tone poem by Richard Strauss. His films are compositions even more than they are stories – they are contemplations of the human condition, explorations of the soul that do not lose their grip on the real world. As with the 2 segments of Kieslowski’s The Decalog that we watched last year, the background for his cinematic canvas is the world as we know it and the dilemmas of life that real people face in the throb of life.

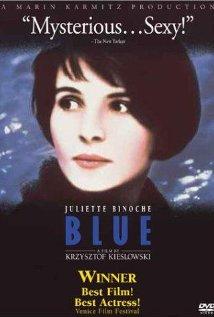

Blue is the first installment of Kieslowski’s majestic Trois Couleurs (Three Colors) trilogy: Blue, White, and Red. The colors are drawn from the French national flag that memorialize the themes of the French Revolution: liberty, equality, and fraternity. Each film is a parable meditating on each of these themes.

Freedom. Often in film literature, freedom is depicted as that liberation realized only in death (Braveheart), or as that throwing off of the chains of repression (Easy Rider). However, in Blue, Kieslowski invites us to think about freedom amid the toil of life, that freedom which will not allow us to escape into self-pity, revenge, or indulgence. In Kieslowski’s own words, “in Blue, liberty is not treated in a social or political way, but [as] the liberty of life itself.”

Julie, the central figure played exquisitely by Juliette Binoche, is “brutally liberated” (Jonathan Kiefer in Salon) in the opening scene when her husband, a renowned composer, and her daughter are killed in an automobile accident. She then systematically disposes of all the relics of her former life, including original drafts of the score her husband left unfinished at his death. “I don’t want any belongings, any memories,” she says. “No friends, no love. Those are all traps.” She escapes to an anonymous life with “no memories, no love, no children.” But she discovers that she cannot be really free – she cannot gain the freedom to control her life simply by burying everything that has been a part of her life that she wants to forget. She is eventually recognized and found, and she admits that all during her self-imposed exile, the music that had been her husband’s inspiration, proved irrepressible within her soul. She completes the unfinished symphony for her husband, and with a quiet realism discovers freedom not as a thing unto itself but as part of the precious fabric of life. While this film and last month’s selection (About a Boy) are quite different, they bring us to very similar conclusions about freedom. Freedom can never be ours when we hoard it to ourselves and claim ownership of it like some trophy. Real freedom can only be known in that ironic tension described by Jesus, when we give ourselves away: “If you cling to your life, you will lose it; but if you give it up for me, you will find it” (Matthew 10:39).

The film is “visually sumptuous” (Kiefer) and plays wondrously on every variation and image of blue imaginable. Blue can be the water in which Julie swims. It can be ink, flowers, or the sparkling crystals in a lamp. Blue is the world that Julie inhabits, and it is only in that world that she can find the freedom in which her soul longs to rest. The emotive palette of the cinematography and the uncluttered study of human character reminds us that this is our world too.

-Steve Froehlich

Questions for discussion:

- How does Julie feel like her life is taken from her?

- How does Julie attempt to reclaim control of her life?

- In what way does Julie’s attempt to gain control comment on your efforts to gain control of life?

- Or, to escape those parts of your life that you believe will keep you from being free?

- Why does Julie give herself sexually to her long-time friend and admirer?

- What convinces Julie that she cannot find what she is looking for by escaping?

- How does Julie express the freedom she finds in the end?

- How do you think the use of color reinforces the theme of the film?

- In what way does the music of the film, musical elements within the film, and music within the character of Julie blend to expand the idea of the film?

- What is freedom?