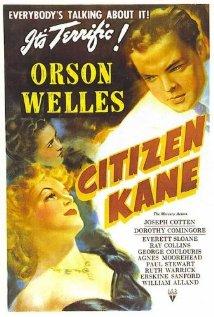

Most essays and reviews of “Citizen Kane” begin with either a haunting question or a bold statement: “Is Citizen Kane the greatest movie ever made?” or “Citizen Kane is undoubtedly the triumph of the American cinema, the greatest American film ever made!”

The origins of “Citizen Kane” are well known. In 1941, Orson Welles, the boy wonder of radio and stage, was given freedom by RKO Radio Pictures to make any picture he wished. Herman Mankiewicz, an experienced screenwriter, collaborated with him on a screenplay originally called “The American.” Its inspiration was the life of William Randolph Hearst, who had put together an empire of newspapers, radio stations, magazines and news services, and then built to himself the flamboyant monument of San Simeon, a castle furnished by rummaging the remains of nations. Hearst was Ted Turner, Rupert Murdoch and Bill Gates rolled up into an enigma.

At the center of the film’s technical brilliance is the cinematography of Gregg Toland, who on John Ford’s “The Long Voyage Home” (1940) had experimented with deep focus photography–with shots where everything was in focus, from the front to the back, so that composition and movement determined where the eye looked first.

The film opens with the death of newspaper magnate, Charles Foster Kane — he slumps over and utters a single final word, “Rosebud.” After a dizzying newsreel overview of Kane’s life and accomplishments, the story of his life is told through the eyes of those who knew him, a series of flashback remembrances. “I don’t think any word can explain a man’s life,” says one of the searchers through the warehouse of treasures which Kane left behind. Yet, the single word, “Rosebud” becomes the one word that unlocks the private world of a larger-than-life citizen. Kane’s business partner explains it this way: “All he really wanted out of life was love. That’s Charlie’s story–how he lost it.”

Roger Ebert (film critic for the Chicago Sun Times) describes the journey the story takes this way: “Citizen Kane” knows the sled is not the answer. It explains what Rosebud is, but not what Rosebud means. The film’s construction shows how our lives, after we are gone, survive only in the memories of others, and those memories butt up against the walls we erect and the roles we play. There is the Kane who made shadow figures with his fingers, and the Kane who hated the traction trust; the Kane who chose his mistress over his marriage and political career, the Kane who entertained millions, the Kane who died alone.

Now more than 60 years since it’s first release, the movie still arrests us by its stark honesty. It dares to preach to us about the human condition, that fame and power do not change what we are at the deepest part of our being, that a life glutted with success and prestige does not answer the lonely longing of a little boy lost within the faade created by media manipulation. Citizen Kane forces us to listen to the plaintive cry of every human soul, “Who will love me?

-Steve Froehlich