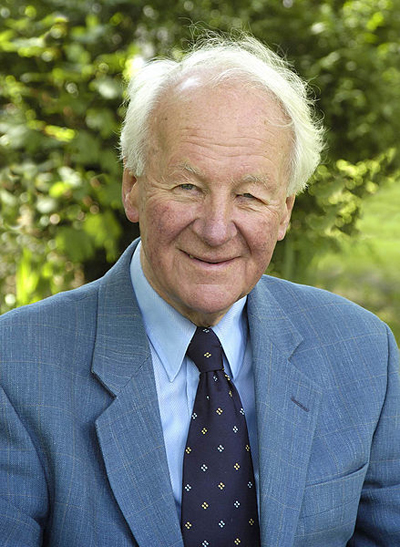

John Stott is an Anglican clergyman, author of many books on Christian discipleship, and one of the most influential Christians in the world. E.O. Wilson is a Harvard biologist, author of many books on sociobiology, and one of the foremost advocates of “scientific humanism” in the world. What do they have in common? By the grace of God, they share a common love for the world that God has made, as evidenced by their mutual respect and endorsement of the work of Peter Harris.

Harris is Founder and President of A Rocha, an international Christian conservation organization that has been described as a cross between L’Abri and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. The story of the founding of A Rocha is told in Harris’s book Under the Bright Wings (Regent College, 1993).

Strangely enough, Christians are sometimes regarded as enemies rather than friends of the natural environment. Renowned conservation biologist David Orr, for example, recently argued that Christians’ apocalyptic eschatology makes them poor stewards of the earth. This is a new twist on the old idea that some people are so heavenly minded as to be no earthly good. Wilson, in his book The Creation (Norton, 2006), makes a similar assumption.

This idea that Christians are poor stewards of creation traces largely an influential 1967 article by historian Lynn White. But according to a recent and definitive review of the literature by Cornell graduate Greg Hitzhusen ’92, PhD ’06, those who find this narrative appealing should not therefore assume it’s true. Environmental destruction, Hitzhusen argues, has been just as evident in Eastern and non-Judeo-Christian lands. “This is not to deny that some Christians hold anti-environmental views; but the claim that Christians do so in significant numbers and primarily because of their religious beliefs is baseless. Simply put, the spectre of biblical anti-environmentalism is largely a myth.”

Although defending Christianity from baseless criticisms matters, what I love about Harris’s work is that he lives it. He is primarily a practitioner. He is as comfortable banding migratory birds and preserving wetlands as he is discussing theology. Harris named the ministry A Rocha because “it seemed to do justice to all that we were planning–the beginning of field studies, geology, and the only sure foundation for the whole of life, the Rock who is Christ.”

John Stott, in his introduction to Under the Bright Wings, describes Harris as a model of integrated Christian discipleship. In contrast to the “disastrous dualisms” of sacred and secular, spiritual and material, soul and body, Harris understands that “the living God of the Bible is the God of both creation and redemption, and is concerned for the totality of our well-being.” Science and theology are the study, respectively, of God’s two books–nature and Scripture. Christian mission thus “embraces everything Christ sends his people into the world to do,” including “entering into other people’s social and environmental reality.”

Far from rendering one of no earthly good, Harris’s work with A Rocha nicely illustrates that heavenly mindedness takes one deeper into earthly service. As C.S. Lewis once put it so well: “[A] continual looking forward to the eternal world is not, as some modern people think, a form of escapism or wishful thinking, but one of the things a Christian is meant to do. It does not mean that we are to leave the present world as it is. If you read history, you will find that the Christians who did most for the present world were just those who thought most of the next.” Concern for the present world in turn gives Christian believers common ground with others, which is why even E.O. Wilson has called Harris’s second book, Kingfisher’s Fire: A Story of Hope for God’s Earth, “a unique and inspiring epic.”

FURTHER READING

Orr’s article is “Armageddon vs. Extinction,” Conservation Biology 19 (2005): 290-292. White’s article is “The Historical Roots of our Ecological Crisis” Science 155 (1967):1203-1207. Hitzhusen’s article, highly recommended for those with an interest in the topic, is “Judeo-Christian theology and the environment: moving beyond scepticism to new sources for environmental education in the United States,” Environmental Education Research 13 (2007): 55-74. The literature on Christianity and the environment is now vast. One recent contribution to the literature by a highly regarded theologian is Richard Bauckham’s The Bible and Ecology: Rediscovering the Community of Creation (Baylor, 2010). See also Karl Johnson’s review of E.O. Wilson’s The Creation.

In addition to the blossoming of publications on Christianity and the environment, there are also more and more organizations committed to the care of creation. See, for example, the Ausable Institute, Restoring Eden, and the Evangelical Environmental Network.

“God, all nature sings thy glory, and thy works proclaim thy might;

ordered vastness in the heavens, ordered course of day and night;

beauty in the changing seasons, beauty in the storming sea;

all the changing moods of nature praise the changeless Trinity.”

— David Clowney