In December 1999, The Economist published its “millennium issue,” including an article entitled “God: After a lengthy career, the Almighty recently passed into history. Or did he?” After a millennium of being on the defensive, the editors wrote that God was very nearly dead, except for the pesky fact that “the corpse just wouldn’t lie down.”

We started Chesterton House that same winter, and some matters did seem rather bleak at the time. Students compartmentalized faith apart from learning. Scholars studied religion primarily as a dependent variable in the lives of believers. And the general giddiness over economic growth further seemed to render religious faith relatively useless.

Not everything about the spiritual landscape has changed over the last decade, but much has. In a speech given one month after 9/11, philosopher Jurgen Habermas called the West a “post-secular” society. “That the world has become postsecular,” Peter Steinfels wrote in the New York Times just one year later, “is now virtually beyond debate” (as evidenced by the loss of the hyphen).

What exactly “postsecular” means is a matter of considerable discussion. In sociological jargon, secularization entails the “privatization” and institutional “differentiation” of faith–e.g. the separation of church and state (and, in the case of public universities, of church and academy). Postsecularism, by contrast, entails “de-privatization” and “de-differentiation”–i.e., a new intermingling among previously more distinct realms such as religion and politics, religion and health, religion and sport, etc. This “religious turn” is apparent not only in areas such as international relations and film, but also in academic disciplines such as history, philosophy, and literary studies (see, for example, the many professional associations that seek to “integrate” faith and learning within particular disciplines).

Postsecularism thus entails the return of religion, and even The Economist’s editors recently produced a volume entitled God is Back: How the Global Revival of Faith Is Changing the World (Penguin, 2009). But this return of religion is not a return to the past. What we now witness is neither the displacement of religion by secularism (as predicted by secularization theory) nor the displacement of secularism by religion (as desired by many persons of faith), but rather the rise of religion amidst continual secularization. Contrary to conventional wisdom, Habermas says, the relationship between religion and secularization is not a zero-sum game.

Sociologist Peter Berger observes that Habermas has experienced a conversion of sorts–not a conversion of faith, but a conversion to the view that Judaism and Christianity are on balance forces for good in the world. In The Dialectics of Secularization: On Reason and Religion (Ignatius, 2007), Habermas identifies Judaeo-Christianity as a resource for reason, individual rights, egalitarianism, and democracy. Whereas he once regarded religion as useless, now it appears useful. (See “What Happens when a Leftist Philosopher Discovers God?”.)

There are indeed hopeful signs of change. Whether the third millennium will be, as the late Pope John Paul II used to say, “a great springtime for Christianity,” we know not. What we do know, as Diane Winston put it in the Chronicle of Higher Education, is that “Like the sexual revolution that swept through campuses beginning in the late 1960s, the current religious revival won’t be stopped by clucking tongues and disapproving glances. It won’t disappear even if we ignore it. Now, as in the past, young people are exploring new ways of believing and behaving in their search for a richer, more meaningful way of being in the world.” The times they are a-changin’.

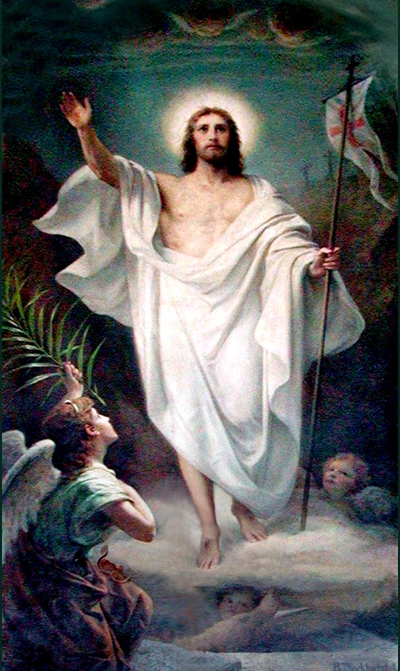

The dilemma, of course, is that for religion to be useful, some must also believe it to be true. Our hope is that the postsecular era will take religion more seriously not only with respect to its social utility but also on its own terms. Given that the corpse of the Almighty just won’t lie down, rumors of resurrection are as relevant as ever.

POSTSCRIPT: April 2012 – Here is an interesting blog post on postsecularism in art.