Category: Movie Review

Lost in Translation

General

General Movie Review

Movie Review

I lost a world the other day.

Has anybody found?

~Emily Dickinson~

So many words; so little understanding.

So many images; so little presence.

So much light; so little warmth.

So many people; so little friendship.

So much solitude; so little peace.

So many distractions; so little happiness.

So many comforts; so little rest.

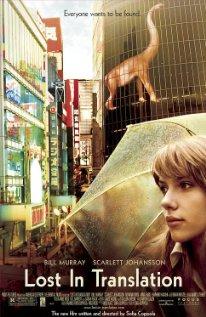

Lost in Translation, an important film for our time, gives words and images to the lost loneliness of our generation. The deep longing of our heart for what we want more than anything, more than sex. To be found, to be understood, to belong, to be human.

Bob (Bill Murray) and Charlotte (Scarlett Johansson), surrounded by all things affluent and larger than life, lonely, meet in the ultramodern Tokyo hotel and share a friendship wrapped in sweet comic sadness. Bob, a famous big-screen actor whose glory is fading, has come to Tokyo to shoot a commercial for Santory whiskey. Has his career come to this? Is he anything more than the digitally-projected image he has created? His media-enriched persona is recognized internationally, but does anyone know who he is? Charlotte, newly married, has come to Tokyo with her husband, a photographer whose driving ambition is capturing the images of rock stars and beautiful people. Has intimacy been lost to infatuation? Will she have value and meaning apart from becoming yet another icon captured in her husband’s lens? Her husband is passionate about immortalizing the fame of celebrities, but will he be content to walk with her in the very mortal world of hopes and hurts?

Lost in Translation is an exquisite film, magnificently conceived and created by Sofia Coppola. This is only her second feature film (The Virgin Suicides, 2000), but she has undoubtedly inherited much from her father, Francis Ford Coppola (Godfather trilogy), a film legend. David Edelstein (Slate) says that she “put the longing for human connection into your bloodstream from the first frame.” Indeed, she does. The performances by Murray and Johansen are tremendous — certainly Murray’s finest hour worthy of the Oscar nomination awarded him.

As you watch the film, absorb many of its subtle elements. Sound, and the way the noise of the world falls on the ear of someone who is lost and disconnected. Light, and the way the world is illuminated to someone who longs for a hopeful tomorrow. Windows, and what a panoramic view of the world brings to someone who is lonely. Images, and how someone without a certain center is known. Desire, and the hunger for something more than physical gratification. Distance, language, a shirt, a wig, reflections in glass — all these provide harmony to the major melody of Lost in Translation.

Are the faces reflected in the window our own, or perhaps well-crafted projections that mask our true self? Is the ironic laughter floating across the room the sound of a heart longing to be known, loved? The sights and sounds of Lost in Translation are all familiar to the world as we know it, but do we understand what those sights and sounds really mean?

-Steve Froehlich

CONTACT

General

General Movie Review

Movie Review

For the Cornell community, the importance of the film CONTACT goes far beyond the fact that it is based on the 1985 novel by famous Cornell professor and scientiest, Carl Sagan. It is emblematic of issues formative to the founding of the university.

The debate over the relationship between science and religion is a topic that energized the thinking and vision of A.D. White, Cornell’s co-founder and first president. Cornell was founded in 1865 in the first full blush of the Modern Era, and the rise to prominence of Enlightenment Humanism that aggressively pitted naturalism against super-naturalism, and reason against religion (i.e., historic Christianity). In 1896, White published his 2-volume, The History of Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom. White takes over 700 pages to document the success of German Higher Criticism in deconstructing and dehistoricising main-line views of the Bible, Jesus, miracles, and faith in God. Cornell University is (or at least was) the incarnation of his belief that the war was over. Here are some of White’s concluding remarks:

“For all this dissolving away of traditional opinions regarding our sacred literature, there has been a cause far more general and powerful than any which has been given, for it is a cause surrounding and permeating all. This is simply the atmosphere of thought engendered by the development of all sciences during the last three centuries…. Vast masses of myth, legend, marvel, and dogmatic assertion, coming into this atmosphere, have been dissolved and are now dissolving quietly away like icebergs drifted into the Gulf Stream” (716).

“Sciences are giving a new solution to those problems which dogmatic theology has so long labored in vain to solve…. If, then, modern science in general has acted powerfully to dissolve away the theories and dogmas of the older theologic interpretation, it has also been active in a reconstruction and recrystallization of truth; and very powerful in this reconstruction have been the evolution doctrines which have grown out of the thought and work of men like Darwin and Spencer” (717).

Sagan held some very similar views. In short, one might say that White and Sagan believed that scientific ways of knowing trumped revelation, and therefore traditional or “revealed” religion. Yet implicit in their worldview are metaphysical assumptions of a decidedly naturalistic stripe. What comes through White and Sagan then is not “science” pure and simple, but philosophical naturalism–which is itself a kind of religion and a kind of faith. The new “scientific” view of the world turns out to be an ancient philosophical view of the world. It is therefore not surprising that CONTACT returns us to age-old questions:

“Should we take all this on faith? Is there an all-powerful, mysterious God that created the universe, but left us no proof of his existence? Or, is there simply no God, and we created him so we wouldn’t feel so alone?”

Until his death, Carl Sagan worked closely with director Robert Zemeckis (Forrest Gump). The result is a thoughtful exploration not just of space and time, but of these ancient questions. Jody Foster gives a vibrant and mature performace as Dr. Ellie Arroway, a determined scientest who works with SETI (Search for Extra Terrestrial Intelligence). She has spent her life listening with a longing ear turned toward the stars. This is the story about what she hears, and how what she hears changes what she believes about science and about God. Ellie reflects:

“I had an experience I can’t prove, I can’t even explain it, but everything that I know as a human being, everything that I am tells me that it was real. I was part of something wonderful, something that changed me forever; a vision of the Universe that tells us undeniable how tine, and insignificant, and how rare and precious we all are. A vision that tells us we belong to something that is greater than ourselves. That we are not, that none of us are alone. I wish I could share that. I with that everyone, if even for one moment, could feel that awe, and humility, and the hope, but… that continues to be my wish.”

12 Monkeys

General

General Movie Review

Movie Review

“Solving the riddle of 12 Monkeys is an exhilarating challenge,” says Peter Travers of Rolling Stone. Terry Gilliam (Time Bandits, The Fisher King, The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, and The Man Who Killed Don Quixote… well, not quite) has created an apocalyptic puzzle that dismembers time, like a surgeon performing an autopsy, so that we can explore what makes science tick–the science that unravels how the mind works, how the world goes, and how the heart sings. When Cole (Bruce Willis) the time-traveler meets Goines (Brad Pitt) the fingernail-chewing son of a famous virologist, Goines opines, “The problem with science is… it’s not an exact science.”

Cole comes to the past (1996) from the present (2035) with the knowledge that 5 billion people have been extinguished and the surface of the earth rendered uninhabitable by a deadly virus that has been unleashed upon humanity. Cole is a criminal who survived the holocaust because he was isolated in prison, and he is given a mission that may earn him his freedom if successful–he is to return to 1996, find the deadly virus, and bring a sample back to the present (the future) so that it can be analyzed.

Time travel is much more than a clever device in this story–it is a way of tilting our vision of time so that we can think about the role of knowledge and power… of inevitability. Have the survivors, now in control of the ruins of civilization learned anything from the holocaust, or is the cold clinical reality rather that time plus knowledge has not changed them at all? Is knowledge being used as power to make certain the outcomes of history?

Cole, like Cassandra in Greek legend, knows what will happen, yet he is powerless to convince anyone that what he knows is true. Cole is surrounded by those who would use their knowledge to control the future. Psychologist Kathryn Railly (Madeleine Stowe), whose relationship with Cole moves from clinical detachment to loving compassion, eventually questions the science behind her psychological expertise: “I mean, psychiatry: it’s the latest religion. We decide what’s right and wrong. We decide who’s crazy or not. I’m in trouble here. I’m losing my faith.”

Cole speaks like a seer. He knows the future and he hears voices of those who share his knowledge. He is a prophet, yet he is not a messiah. He searches for the secret cult, the 12 Monkeys, the true believers who know that his vision of the future is true. So, what are the 12 Monkeys? Is the symbol used by the group, 12 monkeys arranged in a circle, meant to resemble a clock–time, inevitability, the future, the past. Is the number 12 a prophetic apocalyptic icon? Are the monkeys baring their teeth in mock laughter as if to ask us which side of the cage bars we are on–are we really free… or in the grand evolutionary scheme, have we really progressed all that far?

David Peoples (Unforgiven, Blade Runner) and his wife, Janet, worked from Chris Marker’s 1962 short film La JetTe, a classic piece of French avant-garde cinema, to create a screenplay filled with their own vision of a future haunted by the past. Terry Gilliam has created a haunting visual story filled with images and ideas that will linger in your mind and draw you back for a 2nd look, a 3rd look… Great films and great filmmakers have the power to do that.

-Steve Froehlich

About a Boy

General

General Movie Review

Movie Review

Will Freeman is a the character we suspected has been tucked behind the veneer of the superficial personalities embodied by Hugh Grant in many of his films. He is, as James Berardinelli so neatly describes, “the ultimate slacker. Living off the royalties of his one-hit-wonder father’s Christmastime jingle ‘Santa’s Supersleigh’, Will is proud of never having had a job or, indeed, having done much of anything. He’s not interested in a serious relationship–casual sex and one-night stands are his forté. Then, one day, he makes a mistake. On the prowl for easy female prey, he ventures into a single parents’ group meeting. Soon, he is dating a woman who is babysitting for her friend’s son, Marcus (Nicholas Hoult). This wouldn’t mean much to Will, except that Marcus takes a liking to him and decides that Will might be the perfect match for his emotionally disturbed mother, Fiona (Toni Collette). Then the strangest thing happens–Will and Marcus strike up an unusual friendship. But complications ensue when Will falls for another single mother (Rachel Weisz) and wants Marcus to pretend to be his son.”

There it is–a simple, even familiar, plot line. However, what draws us into this film based on a novel by Nick Hornby (his work also was the premise for High Fidelity), what hooks us is the realization that we are looking at 2 children–one is truly a child, Marcus, while other is a 38-year old child, Will. Will has every boredom-eliminating toy imaginable, yet is lonely, seemingly incapable of thinking of anyone other than himself. In a futile pretence of squeezing some sort of meaning into his empty life, Will divides his existence into half-hour increments and vows never to mean anything to anyone. He declares himself to be an island, and ponders, “How do people manage to fit in a full-time job?” He looks at life as “the Will show,” which is not an “ensemble drama.” He is in every way clueless, selfish, and immature.

The irony of the story is that Marcus, who scratches his way through a bullied life at school and an emotionally terrorized life at home (his depressed mother is suicidal), knows that the one thing he desperately needs is one stable parent. Ok, an older person who looks like a parent. And, yes, it’s ok that he happens to be rich. Marcus has the maturity to press through Will’s immaturity to make the father-son connection stick. That is the heart of this charming film.

The name, Will Freeman, says something to us about the commentary this character makes about our lives and priorities. Will has the appearance of freedom. He can do what he will. He is an Everyman. He is the caricature of what is held up as the icon of success. He has arrived materially, but his soul remains lost in the woods. Not only is he a lost soul, but he has a terrible time understanding the real dilemma of his condition–he has bought into the pretense of life so deeply he has mistaken it for the real thing. Marcus’ life is a surreal rollercoaster and a prison at the same time. He wants to be free. He wants to be found. But he knows that it must come as a gift from someone who is willing to love him.

This story parallels the classic Beauty and the Beast tale in which the Beast has to learn that he is a beast. But Will, the teen-idol beast in this film, represents much of what we as a culture value and aspire to be–at first glimpse, he doesn’t look beastly. But his bored life is laughable, comic, and so are our lives when we chase what he chases.

About a Boy, directed by Paul and Chris Weitz, teases out the meaning of Jesus’ words: “Whoever finds his life will lose it, and whoever loses his life for my sake will find it” (Matthew 10:39). When Will and Marcus give to each other and receive from one another the gift of honest and mature friendship, we cheer.

-Steve Froehlich

Questions for discussion:

- Will values living as an island. In what ways do we either value or permit ourselves to be drawn into lives of isolation?

- How keeps us from making real, giving friendships?

- Why do you need friendships – what aspects of your life or experiences in your life have convinced you that you must form significant friendships?

- Will is a user. In what ways do you use people simply to get what you want? Marcus is a fighter. In what ways have fought desperately for what you know is of great value in your life? Once you got it or reached your goal, was it worth the means you employed to get there?

- Why do you think God designed humans to forge deep human relationships? What does that need or those friendships teach us about God?

- Will pretended to be busy so that he would have an excuse for not becoming attached to people around him. In what ways do we busy ourselves in the same way? Once Will’s eyes are open to the world around him, once our eyes are opened, what are some of the things he and we see that we’ve been missing?

- What makes a friendship mature and significant?

Autumn-Spring

General

General Movie Review

Movie Review

It sounds much too bland to ask: How would you live today if you knew that it were your last? For someone who really did care about squeezing every drop of living out of life, the proposition must be framed with much more imagination. For instance, Is the joy of watching the poor bus driver go into a wild-eyed panic because you have stepped out in front of his oncoming bus a fair exchange for the very real possibility of have having your ticket permanently punched a few days early? Frantisek Hána (Fanda) would have to give it serious consideration. It would be quite a show, one worth seeing. If he took that step off the curb, you can be sure he would stand facing the mayhem bearing down upon him with a bemused calm that would allow him to absorb the full effect of his mischief.

Autumn-Spring is a gem of Czeck cinema featuring the acclaimed veteran duo of Vlastimil Brodsk and Stella Zázvorková as Fanda and Emílie, roles for which they were awarded the Czeck Lion. The married couple is in their autumn years. Emílie insists on using their time and resources for the practical necessities of preparing for the inevitable so that they are not a burden on anyone else. Fanda, however, is stoical about such mundane matters—his imagination and playfulness are alive even inside his aging body and he will have nothing to do with living practically and “going quietly into that good night.” He and his all-too-willing accomplice, Eda, are busy scheming up their shenanigans: posing as subway agents so they can steal kisses from pretty passengers who don’t have the proper fair, posing as a retired opera conductor and assistant while allowing greedy real estate agents wine them and dine them in hopes of a lucrative sale.

This is a film touched by the Eastern European pessimism or sadness that comes from nearly a century lived in oppression. The actors themselves have weathered their homeland’s bleak hours, so their performances function as a somewhat unintentional testimonial to people who have waited to die well. The film assumes that death is inevitable—that much is not in debate. But it does ask us how we will live, regardless of our age, as people who are dying.

Fanda doesn’t really want to cheat death—he simply does not want to give up on the joy of life a moment too soon. However, his determined refusal to be practical exposes a deep root of selfishness and self-centeredness. His own thrill-seeking and joy-riding eventually reveal how unwilling he has been to be loving toward others, especially his loyal and persevering wife.

Autumn-Spring shows us Fanda and Emílie having grown old together, but it is not essentially a film about old age or death, although death is always present. In a much more charming and often amusing manner it echoes the line from William Wallace in Braveheart: “Every man dies, but not every man really lives.” It reminds us of the power which humor, imagination, and joy have to literally sustain our lives. It asks us to think about the relationship that love and personal happiness have to one another.

Director Vladimír Michálek gives us a simple unadorned film so that the characters come alive with depth and dimension. Yet, the simplicity functions as a powerful reminder that great joy in life does not come from those distractions that often complicate our lives. Childlike Fanda uses only his imagination to make a playground out of a world which knows little of the adult gadgets and toys that keep us busy and distracted, weary in our drivenness.

The film’s subtitles are well-translated and capture much of the nuance expressed in the story and in the rich facial expressions of the characters. One of the great ironies of this hopeful and affirming film is that it marks the end of the life and career of Vlastimil Brodsk—he committed suicide shortly after the film was completed.

-Steve Froehlich

Questions for discussion:

- How does the film’s simplicity complement the theme of happiness?

- Why do you think Fanda is so indifferent to Emílie?

- Why do you think Emílie is so angry with Fanda?

- What is the source of the undercurrent of cynicism in the film?

- How and why do Fanda and Emílie change, if in fact you think they do?

- How does the film enlist your sympathies for the characters? Do your sympathies change? Why?

- Do you think the film is hopeful? Why, or why not?

- How does the film explore the tension between possibility and necessity? Between truth and happiness?

Big Fish

General

General Movie Review

Movie Review

How will you tell the story of your life? How will you capture and remember the people, the moments that are the unfolding drama of life? Is there a story in your life worth telling?

Big Fish, directed by Tim Burton and adapted from a Daniel Wallace novel by John August (Charlie’s Angels, Charlie’s Angels: Full Throttle), is a fairy tale – heroic, romantic, and fantastic. It is about the telling of one man’s life, Edward Bloom (Ewan McGregor, Albert Finney). Edward has narrated his life through a string of unbelievable tales, stories he has told a thousand times and which his son, Will (Billy Crudup), can recite by heart… with disdain. Now that Edward is dying, Will wants to discover the truth about who his father really is – he wants to uncover the man behind the myths, or as Will insists on referring to the stories, “the lies.” “In telling the story of my father’s life, it’s impossible to separate fact from fiction, the man from the myth.”

Matthew Kirby (www.metaphilm.com) describes Big Fish as “a tall tale about the necessity of fiction if there is to be any truth in the world.” Exactly. James Berardinelli (Reelviews) writes, “In addition to telling a wonderful fairy tale, Burton is lauding the importance of storytelling and emphasizing the need to keep some element of magic and mystery in a world that has become coldly cynical.” The great irony of the film and the heart of the film’s metaphor is that the myths reveal the real Edward. Big Fish is a cinematic fairy tale about the transforming power of art.

The title calls to mind the wistful fisherman telling the tale of how the big one got away. Who is the “big fish”? How is the fish caught, and how is the fish set free?

The cinematic world of Tim Burton is a quirky blend of fantasy and reality (Batman, Batman Returns, Edward Scissorhands, Sleepy Hollow) – the surreal mingles with the real often creating a jarring, rejuvenated view of the familiar. Burton’s films are often dark and cynical, but Big Fish is a hopeful and noble story infused with a determined idealism. The confidence and optimism of the tale, actually of Edward’s life, is the answer to a question posed early in the film: How would you live your life if you knew today how your life would end?

Big Fish features a splendid blend of characters and performances by Albert Finney as the older Edward Bloom, Jessica Lange as the older Sandra Bloom, Ewan McGregor as the younger Edward, Danny DeVito, Helena Bonham Carter, Steve Buscemi, and Robert Guillaume. The film is beautifully shot and edited, and glides effortlessly between the reality of fantasy and the fantasy of reality. Burton has given us a celebration of the art of storytelling and the storymaking of love.

-Steve Froehlich

Questions for discussion:

- Big fish in a small pond… The big one that got away – how do these familiar expressions fit into the story of the film?

- How does the element of water figure into the imagery and ideas of the story?

- Is Edward Bloom self-centered or unselfish? What leads you to that conclusion?

- What motivates Edward to live his life the way he has?

Blue

General

General Movie Review

Movie Review

Watching any of the films by Krzysztof Kieslowski is like meditating upon an impressionist painting by Renoir or being embraced by a tone poem by Richard Strauss. His films are compositions even more than they are stories – they are contemplations of the human condition, explorations of the soul that do not lose their grip on the real world. As with the 2 segments of Kieslowski’s The Decalog that we watched last year, the background for his cinematic canvas is the world as we know it and the dilemmas of life that real people face in the throb of life.

Blue is the first installment of Kieslowski’s majestic Trois Couleurs (Three Colors) trilogy: Blue, White, and Red. The colors are drawn from the French national flag that memorialize the themes of the French Revolution: liberty, equality, and fraternity. Each film is a parable meditating on each of these themes.

Freedom. Often in film literature, freedom is depicted as that liberation realized only in death (Braveheart), or as that throwing off of the chains of repression (Easy Rider). However, in Blue, Kieslowski invites us to think about freedom amid the toil of life, that freedom which will not allow us to escape into self-pity, revenge, or indulgence. In Kieslowski’s own words, “in Blue, liberty is not treated in a social or political way, but [as] the liberty of life itself.”

Julie, the central figure played exquisitely by Juliette Binoche, is “brutally liberated” (Jonathan Kiefer in Salon) in the opening scene when her husband, a renowned composer, and her daughter are killed in an automobile accident. She then systematically disposes of all the relics of her former life, including original drafts of the score her husband left unfinished at his death. “I don’t want any belongings, any memories,” she says. “No friends, no love. Those are all traps.” She escapes to an anonymous life with “no memories, no love, no children.” But she discovers that she cannot be really free – she cannot gain the freedom to control her life simply by burying everything that has been a part of her life that she wants to forget. She is eventually recognized and found, and she admits that all during her self-imposed exile, the music that had been her husband’s inspiration, proved irrepressible within her soul. She completes the unfinished symphony for her husband, and with a quiet realism discovers freedom not as a thing unto itself but as part of the precious fabric of life. While this film and last month’s selection (About a Boy) are quite different, they bring us to very similar conclusions about freedom. Freedom can never be ours when we hoard it to ourselves and claim ownership of it like some trophy. Real freedom can only be known in that ironic tension described by Jesus, when we give ourselves away: “If you cling to your life, you will lose it; but if you give it up for me, you will find it” (Matthew 10:39).

The film is “visually sumptuous” (Kiefer) and plays wondrously on every variation and image of blue imaginable. Blue can be the water in which Julie swims. It can be ink, flowers, or the sparkling crystals in a lamp. Blue is the world that Julie inhabits, and it is only in that world that she can find the freedom in which her soul longs to rest. The emotive palette of the cinematography and the uncluttered study of human character reminds us that this is our world too.

-Steve Froehlich

Questions for discussion:

- How does Julie feel like her life is taken from her?

- How does Julie attempt to reclaim control of her life?

- In what way does Julie’s attempt to gain control comment on your efforts to gain control of life?

- Or, to escape those parts of your life that you believe will keep you from being free?

- Why does Julie give herself sexually to her long-time friend and admirer?

- What convinces Julie that she cannot find what she is looking for by escaping?

- How does Julie express the freedom she finds in the end?

- How do you think the use of color reinforces the theme of the film?

- In what way does the music of the film, musical elements within the film, and music within the character of Julie blend to expand the idea of the film?

- What is freedom?

Chocolat

General

General Movie Review

Movie Review

Chocolat is sinfully scrumptious cinema. Rarely does a film look good enough to eat, but Lasse Hallstrom (My Life as a Dog, What’s Eating Gilbert Grape?) gives us a fairy tale that will tease your taste buds. Really. But feast your eyes — you won’t do any damage to your waistline.

Set in an idyllic French country village in 1959, Chocolat tells a simple story, a fable. Once upon a time, a “sly wind from the North” blows the beautiful gypsy, Vianne (Juliette Binoche), and her daughter, Anouk, into the village. Their arrival, just in time for Lent, disrupts the ancient ordered way of life. The Mayor, the Counte de Reynard (Alfred Molina), is the self-appointed moral authority of the community. He even scripts and rehearses Father Henri’s Lenten homilies which call for “abstinence, reflection, and sincere penitence.”

Vianna shocks and startles the staid community by her indifference to the Mayor’s conventions and intimidation. She is an unwed mother. She does not attend church. She brazenly opens her chocolaterie — her tantalizing and seductive treats, her ancient recipes, boldly and temptingly set on display for all the the penitent and sober worshippers to long for as they wind their way to the church.

Therein lies the conflict and questions of the film. Does God approve of pleasure? Are joy and Christianity incompatible? Is religion repressive? Does the Christian faith offer any hope that hurting people can find healing for the deep longing of the human spirit?

Ironically, the one who brings joy is herself haunted by sadness, the weariness of being blown by the wind and never being truly at home, the ache of shame and rejection. But Vianna meets a river wanderer, Roux (Johnny Depp), and the gifts of kindness and loyalty that he offers her have the same magical effect upon Vianna that her chocolates have upon the good people of the village.

This is a fairy tale in which a cup of hot chocolate can soothe away an old woman’s fear of dying, chocolate covered almonds can tame the anger of a selfish husband, and truffles can give a lad courage. This is a romanticized reminder that age-old gnostic asceticism is still with us and still has the power to crush and wound even the most delectable of God’s creations, men and women who bear the glory of his image. Chocolat, much like Babette’s Feast, invites us to contemplate what life would be like without beauty and the joy of delighting in good things.

-Steve Froehlich

Bruce Almighty

General

General Movie Review

Movie Review

“I don’t need to sit here and explain this movie to you, do I?” So opens the review of Bruce Almighty by Christopher Null of filmcritic.com. He has a point. The film concept is painfully simple, and the point is glaringly obvious. Isn’t it? So, don’t be prepared for a labyrinth of intellectual exploration or profound psychological musings – that would be diving in the shallow end of the pool only to miss the universally obvious – which is the point.

Just about everyone at some time or in some way, maybe deep down (c’mon, fess up), has thought about how life would be better if she were God or if he were in charge just for a day to set things straight. It’s true. Alice Cooper sings the confession for all of us in “I Just Wanna Be God”

I’m in control

I got a bulletproof soul

And I’m full of self-esteem

I invented myself with no one’s help

I’m a prototype supreme

I sit on my private throne

And run my lifestyle all alone

Me, myself and I agree

We don’t need nobody else

I’m just trying to be God

I only wanna be God

I just wanna be God

Why can’t I be God

Maybe watching the rubbery improvisational antics of Jim Carrey as Bruce Nolan, goofy local TV reporter from Buffalo, will cajole us into agreeing: I just wanna be God.

Tom Shadyac (Liar, Liar; Ace Ventura: Pet Detective; The Nutty Professor) unleashes Carrey in a frolicking comic playground, and Carrey delivers nicely. Jennifer Anniston counters as Bruce’s girlfriend, Grace, and her steady and earnest focus keeps the story from skipping across Lake Erie. Morgan Freeman brings an easy and amiable maturity to the setting as God. Sometimes bemused, often genial, at moments sad, Freeman assures us that God is always in control even when he shares his power with Bruce.

The question is simple: Could I do a better job than God in running the world – ok, not the world, just my little corner of the world? The complexity of the world makes the question absurd, yet why do we still want to try? Why do we still keep reaching for the controls? Why do we still keep shaking our fist at God, or our idea of God, when we confront the circumstances of life that don’t go our way or which we think should turn out differently (and certainly would if we were in charge)?

Do we really need someone to explain it to us? If we are even a little bit honest don’t we have to recognize that there are only 2 options: either God is God, or I am God? The truth is that we don’t understand everything that happens in life when God is God. But the alternative, even when we have great power, is that we are selfish and foolish and destructive when we are God. The alternative is laughable, but when we see ourselves on the screen, will we laugh at ourselves?

In the end, Bruce needs 2 people in his life: God and Grace. Is it any different for us?

-Steve Froehlich

Questions for discussion:

- If you had the power, what would you change about your life, the world?

- Why are we often angry at God?

- Where do our ideas of who God is and what God is supposed to do come from?

- In what ways have you tried to take control of your life? What have been the results?

- What is success?

- In way does Bruce’s use of power comment on the way you would use power?

- Have you ever discovered in yourself a deeply rooted selfishness? How was it exposed?

- What is grace? How does the theme of grace relate to the moral of this comic parable?