Category: Movie Review

Wit

Movie Review

Movie Review

Vivian. From the 1400-1500 Middle English (derived from the French vitalis, “to live,” and vit, “a life”). Vivian Bearing, as her names suggests, has lived life with drive and nobility, perhaps even a life that has been excessively bearing. Over bearing. She is a formidable, distinguished professor of English Metaphysical poetry renowned for her steely, intimidating rigor. She is a scholar specializing in the Holy Sonnets of John Donne. Now, she is dying. Stage 4 ovarian cancer. “There is no stage 5.” Now, she is research. Once she was the ruthless examiner of literature, of words, of detail down to the weight of a single comma. Now, she is the body under examination. The significance of her life has been reduced to her ability to endure being battered not by the “three-personed God,” but by the impersonal violations of her medical data-gatherers, “Pharisaical Dissemblers [who] feigne devotion.” Once she was willing to sacrifice life for the greater good of greater knowledge. Now, from the factual finality and sterile solitude of her hospital bed, she would gladly trade it all for the comfort and dignity of being known.

Emma Thompson gives us a gripping and exhausting performance as Professor Bearing. Thompson, in collaboration with director Mike Nichols, adapted Wit from the stage play by Margaret Edson. The stage, or more properly, the hospital bed, belongs to Thompson and her riveting creation of Vivian Bearing. The medical researchers observe Professor Bearing’s body being devoured by cancer with detached interest and professional delight. We the audience can only watch helplessly. The cancer, as is the subject of Donne’s sonnets Bearing observes clinically, “appears to be a matter of life and death.” But as the reality of her condition becomes increasingly person, Bearing begins to look at herself and her life differently:

This is my play’s last scene; here heavens appoint

My pilgrimage’s last mile; and my race

Idly, yet quickly run Hath this last pace

My span’s last inch, my minute’s last point

And gluttonous death will instantly unjoint

My body and soul….

John Donne… I’ve always particularly liked that poem. In the abstract. Now I find the image of my minute’s last point, a little too, shall we say… pointed. I don’t mean to complain but I am becoming very sick. Very sick. Ultimately sick, as it were. In everything I have done, I have been steadfast. Resolute. Some would say in the extreme. Now, as you can see, I am distinguishing myself in illness.

The film is entitled, “Wit.” Wit refers to a quality of metaphysical poetry, and (in that sense) the title is itself a bit of metaphysical poetic wit. Samuel Johnson describes this sort of wit as “dissimilar images… yoked by violence together” so that the reader is startled out of complacency and forced to think through the argument of the poem. A literary dictionary explains that the use of wit “reveal[s] a play of intellect, often resulting in puns, paradoxes, and humorous comparisons.” John Donne was considered the master of wit. Does he not draw out a wry smile when he prays to God as slave-master and liberator: “Take me to you, imprison me, for I Except you enthrall me, never shall be free.”

Vivian Bearing is now herself a violent collision of life and death, of knowledge and life, of ideal and reality, of student and teacher, of scholarship and love. Donne brings his poetic images together to offer us insight, understanding, and meaning. Wit allows us to observe a scholar, who knows Donne’s poetry exhaustively, “unjointed” by the collision of life and death. The question beneath her struggle is whether what she knows so well (Donne’s sonnets) will bring her understanding and rest. Is there a way to live and die with wit?

As you prepare to watch and discuss this film, take some time to consider Donne’s most famous Holy Sonnet, “Death Be Not Proud”

Death be not proud, though some have called thee

Mighty and dreadfull, for, thou art not so,

For, those, whom thou think’st, thou dost overthrow,

Die not, poore death, nor yet canst thou kill me.

From rest and sleepe, which but thy pictures bee,

Much pleasure, then from thee, much more must flow,

And soonest our best men with thee doe goe,

Rest of their bones, and soules deliverie.

Thou art slave to Fate, Chance, kings, and desperate men,

And dost with poyson, warre, and sicknesse dwell,

And poppie, or charmes can make us sleepe as well,

And better then thy stroake; why swell’st thou then;

One short sleepe past, wee wake eternally,

And death shall be no more; death, thou shalt die.

-Steve Froehlich

Get Low

Movie Review

Movie Review

A folk legend come to life – that’s Get Low starring Robert Duvall as Felix Bush. As the legend goes, in the 1930s in the mountains of TN, a man threw his own funeral so he could enjoy it before he died. Upon learning of the death of an old acquaintance, Felix decides that he will throw a funeral party on the condition that those who come tell a story about him. He’s hoping the truth will come out about his life, a truth that includes something in the past that has driven him into self-imposed isolation. The film is less about the revelation of that past event than it is the need for Felix to be the one to tell his own story—no easy task given his shame and confusion. But for 40 years, Felix has lived a detached life knowing that people have made up all sorts of horrible stories about what kind of a fearful and evil person he must be.

A folk legend come to life – that’s Get Low starring Robert Duvall as Felix Bush. As the legend goes, in the 1930s in the mountains of TN, a man threw his own funeral so he could enjoy it before he died. Upon learning of the death of an old acquaintance, Felix decides that he will throw a funeral party on the condition that those who come tell a story about him. He’s hoping the truth will come out about his life, a truth that includes something in the past that has driven him into self-imposed isolation. The film is less about the revelation of that past event than it is the need for Felix to be the one to tell his own story—no easy task given his shame and confusion. But for 40 years, Felix has lived a detached life knowing that people have made up all sorts of horrible stories about what kind of a fearful and evil person he must be.

One of the beautiful metaphors in the film comes from Felix’s skill as a carpenter. He has built his home in the woods with remarkably well-crafted furniture. He built the small country church served by his long-time pastor-friend, Charlie Jackson. Now, he’s building his own funeral memorial. But what has he made with his skilled hands – has he made a prison or a sanctuary?

Duvall (79 when the movie was made in 2010) gives us another of his magnificent character studies, a hallmark of the latest chapter in his more-than-50-year career in film. He is supported winsomely by Bill Murray as Frank Quinn, who arranges Felix’s funeral party – Murray gives us a believable morally unsteady funeral director who will do just about anything to make a buck. Sissy Spacek gives us Mattie Darrow, a widow who has known Felix in their youth, and having survived her own sorrows, has her own suspicions of Felix’s past. Bill Cobbs is Rev. Charlie Jackson who says of Felix, “I talked to God a lot about you over the years. He said he broke the mold when he made you, said you sure were entertaining to watch—but way too much trouble.”

Get Low invites us to think about honesty and confession as it reflects on how Felix Bush has lived his life knowing that he has failed. It’s a simple morality tale told in rustic tones and elegant cinematography – the visual beauty contrasts with the hidden ugliness while the story muses about how that beauty would change were the ugliness to be revealed. Get Low speaks to the humility needed in death, admitting the inevitable and inescapable, while exploring all that must be done in the life… as long as we have this life to live. This deeply human tale touches on our very common impulse to cover what we do not like about our lives, our sin and failures. But does the gospel of Christ offer a better way, a way of hope?

-Steve Froelich

Les Misérables

General

General Movie Review

Movie Review

Grace in the Raw

Before attending Les Misérables, I heard from a friend–a long-time fan of the stage musical–that she found the rawness of the cinematography distracted her from the music. Armed with this observation, I did not expect to be as ravished by the film as I was. Most captivating is the way in which the musical and filmic elements work together to create a deeply engaging experience of the narrative and its characters that spills over into life, especially through the portrayal of grace.

Film settings necessarily contrast with the expectations established by stage dramas. Many film interpretations of musicals retain a relatively theatrical setting and the perceptual distance of a stage drama. To say that Les Misérables abandons any theatrical effect would be to entirely mistake the film, but nevertheless, the film takes advantage of the medium’s capabilities. The city is shown in various states of disarray: the prostitutes appear ill, the poor look starved and cold, the inn is chaotic, the streets are dirty. Aerial shots are juxtaposed with extreme close-ups to create a continuum of varied perspectives on the story. The close-ups are especially raw, introducing us to the vulnerability of the characters in an intimate way that is downright uncomfortable. Les Misérables thus eliminates the lens of ironic distance common to popular postmodern perception, much to the chagrin of critics. Put differently, it dares to “treat old untrendy human troubles and emotions with reverence and conviction” (Stanley Fish; NY Times).

Trained musicians tend to disparage the quality of the vocals in this film. Although Anne Hathaway presented a stunning performance as Fantine, other leads have come under some severe criticism. However, with the possible exception of Russell Crowe, I think the vocal issues are balanced and even, perhaps justified, by the circumstances in which the characters find themselves; the raggedness of the physical and emotional states of the characters is much more pronounced in this film than it could be on stage, and the rough edges in the vocals are generally appropriate to the dramatic situation. This trained musician finds that the vocal imperfections contribute to the film’s powerful effect.

One might think a film offers little advantage over a staged production with respect to large ensemble numbers, usually staged as a colorful choreographic spectacle. Yet this film production of Les Misérables balances the spectacle and the underlying character of the events portrayed. Take, for example, “Lovely Ladies,” in which shots of the whole group of prostitutes dancing are juxtaposed with disorienting footage of Fantine as she winds her way through the chaos and is swallowed up by it. The scene becomes grotesque and disturbing–the crude humor of the lyrics offset by Fantine’s desperation. We are not supposed to laugh and the film makes laughing impossible.

Consider also the intriguing contrast between musical time and the “real” time of the narrative. In Fantine’s “I Dreamed a Dream” and Jean val Jean’s “Bring Him Home,” all else comes to a halt. No other characters hear these songs; they are reflections, prayers, asides. This feature is not unique to musical dramas but is perhaps most pronounced in them because words take time to sing and are often repeated in a way that would be nonsensical if unaccompanied by music. The realism of the film setting is what makes these pauses in the narrative so emotionally striking. Combined with improbably close-up cinematography and realistic expression, these “slow” moments drag us into the characters’ inner reality.

Many reviewers have remarked on the pervasive theme of grace in Les Misérables. Here again, the film’s interwoven cinematographic and musical elements provide a suitable lens. The grace of Les Misérables is visceral rather than philosophical. We cannot distance ourselves from the ragged horror of the characters’ circumstances and experience, but are rather invited – even compelled – to empathize with and extend grace to Fantine and val Jean, Marius and the young rebels, even Javert. These are sinners all, yet desperately craving mercy. Freed of ironic distance, do we recognize our own desperate need for grace? Are we not also inspired to empathize with, extend grace to, and even act on behalf of our fellow image-bearers who are suffering in the world around us? The epilogue articulates what it might mean for grace to be extended, for all things to be reconciled, at the moment when Jean val Jean steps into death and encounters the prior dead from the story singing a revised version of “Do you hear the people sing”:

Do you hear the people sing? Lost in the valley of the night.

It is the music of a people who are climbing to the light.

For the wretched of the earth there is a flame that never dies.

Even the darkest night will end and the sun will rise.

They will live again in freedom in the garden of the Lord;

They will walk behind the plough-share, they will put away the sword.

The chain will be broken and all men will have their reward!

-Emma McConnell

Other reviews of interest:

“Les Misérables and Irony” (Quoted above; Opinionator Blog, NYT)

“Two Cheers for Javert” (Cardus blog)

“Law and Les Misérables Revisited” and “Les Misérables Review” (CT)

Emma is a Ph.D. student in Music Theory at the Eastman School of Music. Her research primarily emphasizes narrative analyses of music, and she writes about the challenges of living an integrated life of Christian faith, learning, and musicianship at her blog Pictures on Silence.

Moulin Rouge

General

General Movie Review

Movie Review

The greatest thing

You’ll ever learn

Is just to love

And to be loved in return.

These haunting lyrics from Nat King Cole’s “Nature Boy” weaving their way through Baz Luhrmann’s “hallucinogenic fairy tale” (James Berardinelli), assure us that, whatever else the dazzling and exhausting spectacle of Moulin Rouge may entice us to believe, it is a classic and simple love story. This romance explodes with operatic flair and surges with all the musical passion of Orpheus descending into the dark underworld, pouring out all his persuasive melodies to rescue Eurydice from death. But the first words of the story appear on paper, the typed memories of the writer and idealist, Christian: “This is a story about loveÉ and a boy who wandered so very far from home.” And he tells us the whole story in 6 words: “The woman I loved has died.”

Moulin Rouge is Luhrmann’s third major film (Romeo+Juliet, 1996; Strictly Ballroom, 1996). With his wife, Catherine Martin (production and costume designer), Luhrmann uses every penny of his $53 million budget to create an extravagantly energetic musical. Yes, this is a musical, but it’s not the Sound of Music even though you will hear “The Hills Are Alive.” You’ll also hear “Roxanne,” “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend,” Madonna’s “Material Girl” and “Like a Virgin,” the Beatles’ “All You Need Is Love,” U2’s “In the Name of Love,” Dolly Parton’s “I Will Always Love You,” Elton John and Bernie Taupin’s “Your Song,” and more–all songs of the 20th century, set in 19th century Paris, told in a film that could only belong to the 21st century. Kevin Maynard of Showbiz describes the film as “a postmodern fantasia — it’s impossible to come away feeling like you’ve ever seen anything quite like it.”

Experiencing Moulin Rouge is “like being trapped on an elevator with the circus,” exclaims Roger Ebert. The roller-coaster ride jolts to a stop, you sit paralyzed in terrified awe, and you force out the words, “I want to go again.”

The Moulin Rouge (“the red mill”) of Paris, 1899, was a gaudy icon of Bohemian independence and decadence. The night club chorus line popularized the Cancan while the clientele imbibed the dangerously beautiful absinthe. The Moulin Rouge of history paraded an endless spectacle of distractions and enticements, luring in the bored, the lonely, and the disillusioned with the promise of even greater spectacle — Spectacular, Spectacular! (the name of the play Toulouse Lautrec persuades Christian to write for the woman he loves). The Moulin Rouge seduces with the assurance that the burdens of the real world can be checked at the door. In this whirling frenzy of distracted self-indulgence, Luhrmann brings together Satine (Nicole Kidman) and Christian (Ewan McGregor) under the dizzying spell of Zidler (Jim Broadbent), the ringmaster impresario of the pleasure palace. Satine is the jewel of the Moulin Rouge, aspiring to be more than a showgirl and courtesan. Christian, the aspiring but penniless writer, believes in “truth, beauty, freedom and love” above all else — and he believes his words will set his love free. The opportunity to break free of their worlds lit in the red (Satine) and blue (Christian) lights of their respective stages is illuminated by the natural light of the real world which they discover in the presence of each other’s love.

With the self-conscious, medium-awareness of theatrical innovator, Bertolt Brecht, Luhrmann does not want us to forget that we are watching a film. The opening view draws us through the stage proscenium, past the flickering sepia of antique film, over the model city of Paris with the tilting illuminated windmill, into the staged world of the cabaret. The stage-set rooms, the artificial perfection of the night sky, the outlandish pushing for center stage by the characters (often mugging for the camera), the washes of colored theatre lighting, all remind us that we are watching a film and that the film itself is an icon, a fairy tale, a life within a dream upon a stage all captured on film.

Luhrmann has given us a device so wildly artificial yet filled with sights and sounds that are at home in any century, that what is true and enduring shines through with amazing clarity and brilliance. Genuineness amid superficiality. Sacrifice in the face of extravagance. Selflessness against the backdrop of indulgence. Love triumphing over selfishness. Weighing the value and joy of a lasting and noble ideal against a fleeting adoration that dissolves into the anonymity of passing fancy – the eternal vs the temporal. Gently strengthening the contrast between authenticity and artificiality, Kidman and McGregor actually sing their own songs, and carry the music along with their roles with great strength and resilience. The anachronisms in the way Luhrmann tells the story as we listen to so many voicesÉ so many voices familiar to us, beg us to ask of our own lives – what do we really love and what do we value as real, noble, and true? What do we love, and what are we willing to give for the sake of love? What do we hold onto as timeless and let go of as passing? In what world do we live, the artificial stage of feigned adoration or the painful world of genuine love.

The questions which Moulin Rouge asks are classic and timeless, but the way it asks them is extraordinary. Of this you can be certain: this film is not a casual moviegoing experience.

-Steve Froehlich

The Royal Tenenbaums

General

General Movie Review

Movie Review

The faded family banner still flies atop the peak of the majestic Victorian homestead in which the family Tenenbaum grew up. Well, no. That’s not entirely correct. They never really grew up, and that’s the problem. Each member of the family realized notoriety, even fame and glimpses of glory. But this is no family, and they resemble no family among our acquaintances. They live lives cluttered by the elaborate ornamentation of isolated, self-centered existence. They fit themselves within the borders of a family portrait, yet the only thing they share is a mutual loathing of the family patriarch, Royal Tenenbaum. Yet, as we look into the stylized and eccentric lives of these sad, quirky, and silly people, we recognize a humanness that is common, a plight so ordinary we might miss it were it not drawn large for us upon the creative canvas of Wes Anderson.

This is the 3rd major film from Wes Anderson. The Royal Tenenbaums (2001) follows Bottle Rocket (1996) and Rushmore (1998), both offbeat comedies that focus on precious young people who find themselves out of place in the world, who discover that the world is not ready for their genius. The Royal Tenenbaums was co-written by Anderson’s long-time friend, Owen Wilson, who also appears in the film as the Eli Cash. Cash is the life-long friend and neighbor of the Tenenbaum children–he’s a successful author of western-style fiction even though his talent is panned by the literary critics.

The father of the Tenenbaum family is Royal (Gene Hackman), the smirking, irresponsible, arrogant father who has not lived with or communicated with the family for many years. When we meet him, he is being evicted from the hotel in which he has been living–his credit has run out. The Tenenbaum matriarch is Etheline (Angelica Houston), once celebrated author of a book on parenting child prodigies–all 3 of the Tenebaum children were hailed as geniuses. She now works for the museum and plays contract bridge. The 3 children are Chas (Ben Stiller), Margot (Gwyneth Paltrow), and Richie (Luke Wilson)–they are all neurotic. Chas, the business whiz kid, made his fortune in real estate before he entered high school. He is now a widower, and the paranoid parent of 2 boys. Unable to cope with his fears, he moves back into the family house. Margot wrote a $50,000 prize-winning play when she was in the 9th grade, but locks herself away in the bathroom, alone with her secrets. She decides to move back into the family house. Richie, a world-class tennis player, suffered a meltdown at the finals of the US Open–since then, he’s been traveling the world on cargo ships, until he is summoned home by the news that Royal delivers to Etheline, “I’m dying of stomach cancer.”

He’s not, of course. Royal is lying again. He’s broke, and needs a place to stay. He’s alone and has no one to be the butt of his sarcasm. Nevertheless, the family is reunited, and therein is the question posed: Can these angry, wounded people be friends? Is it possible for them to be a family? As Royal says, “I want my family back.”

There is no doubt in anyone’s mind that he does not deserve to get his family back, and that he is the root cause of the family’s dissolution and excessive dysfunction. He swindled Chas. Margot, not a Tenenbaum by birth, is always introduced by him as “my adopted daughter.” When he talks to his grandsons about their mother, he says, “I’m very sorry for your loss. Your mother was a terribly attractive woman.” Yet, even as we are convinced that Royal has been a terrible father and husband, that he has not yet experienced that deep transformation that will re-orient his attitudes and perspective, we know that he wants the right thing. We find ourselves pulling for him, hoping that somehow, some way, these individuals will find one another and learn how to love one another. There is a strong sympathy holding this story together, an urgency that breathes with frequent smiles and occasional outright laughter.

Anderson presents these characters to us–in a way, he shoves them in our face, and we see them as individuals, and we see through them. They each have their own room in the big house, rooms that are so different that each is like a private universe. They tell us their own private stories disconnected from those closest to them. They have all broken away from the home, have all been driven away from the home before the story begins. But now to find themselves they must pick up the threads back at the place where they were broken. As an ironic foil, Eli Cash, an outsider, wants the fame of the family and the talent that his friends possess. Consequently, his life has been spent trying to get into the family just as vigorously as the children have been trying to get out. He wants those impersonal superficial things that have driven the family apart. In the end, he gets what his friends are willing to give him: love.

Is redemption, reconciliation, and forgiveness possible? Royal stumbles forward in his own misguided way. As you watch this process unfold, watch how Royal begins to take his children out of the surreal existence under the roof of the old house and out into the real world. Observe how death plays a central role in the process of change. Each one of the characters must face death. In each character’s life, something must die. Anderson gives us some delightful and funny images that tease out the death theme. But don’t let the humor distract you from the important role it plays in the larger message of redemption. The uncomfortable sexual tension between Richie and Margot makes us feel how confused this family is about understanding, experiencing, and expressing love.

The cast is marvelous with crisp, thoughtful, nuanced performances by each one. Hackman is brilliant. The script and dialogue are understated so that the humor is wry not slapstick. The film is stylized – the episodes framed like portraits conveying the detached impersonal world of the characters. Each portrait is filled with the fascinating details that tell us something about the room occupied by each character. The clothes worn by the characters are like costumes or symbols. The tone of the film is gentle and sympathetic–it does not mock these characters for their troubles and their foibles, but it understands them. So will we if we listen, because these are people like us, people in need of grace, redemption, and healing. We are people who need to come home to find that for which our hearts have been longing.

-Steve Froehlich

Questions for discussion:

- Why is the film titled, The Royal Tenenbaums?

- Why have the characters left the homestead? From what are they running, or what are they unwilling to face?

- How are the images and how is the theme of death used to advance the theme of healing, forgiveness, and reconciliation?

- How does the family home function as a metaphor for the lives of the people who live in that house?

- What role does risk-taking play in the commentary of the story and in the transformation of the characters?

- What significance do you place on the opening and closing image of Mordecai?

- How does our discomfort at the sexual tension between Richie and Margot help us understand the film’s depiction of how love is recognized and expressed? Comment on the different ways Richie shows love to Royal, Margot, and Eli, as well as the other characters’ reaction to that demonstration.

- Why is it meaningful for Richie to put the boar’s head back on the wall? (Note that the wall still has the marks of where it once hung, and remember the scene in which the boar’s head is discovered.)

- How does Royal change, and how does his change influence the members of the family?

- Is there forgiveness and healing? Is it experienced uniformly among the family? If it is experienced at all, is it warranted?

- To what Bible passage or story does your reflection on this film take you? Why?

Unbreakable

General

General Movie Review

Movie Review

Aristotle, in his Poetics, describes the classic literary hero falling from greatness when a tragic flaw is exposed. The story, then, is the struggle to reclaim the heights, wiser and nobler than before. This is the stuff of legends from Ulysses to Hamlet to Darth Vader.

Our appreciation for heroes in everyday life has been renewed by the tragedy suffered on 9/11. Many are singing praises and wreathing accolades to fire fighters, police officers, and ordinary Joes who have risked and given their lives in acts of impulsive courage and selfless daring.

Who are your heroes? What does it take to be a hero? Could you be a hero?

In Unbreakable M. Night Shyamalan takes this important, personal, and epic theme and tells a story much in the same style and tone of his blockbuster sensation, The Sixth Sense. David Dunn, thoughtfully and honestly portrayed by Bruce Willis, is a guard for a local security company. He is struggling to find his place in the world as a husband, father, and man. Elijah Price, played with riveting intensity by Samuel Jackson, is a collector of classic comic books. He is known as “Mr Glass” by those who know of his rare disease that makes bones fragile and brittle. The two men meet after David is the sole survivor of a commuter train derailment – he walks away from the heaps of steaming wreckage without a scratch. Yet both men are deeply broken, and long for a place to belong and call home.

The story unfolds as Elijah observes, “Real life doesn’t fit into little boxes that were drawn for it.” He muses intently about the possibility that our lives are connected to some larger reality, the greatness and the idealism that survives only in comic book heroes and villains. Shyamalan gives us a compelling and deliberate character study of flawed individuals with astonishing gifts. Superbly crafted and photographed, elegantly directly, subtle, refined, puzzling, personal, mysterious – Unbreakable invites us to think about what it means to be noble, to know the satisfaction of being valued by someone else, of donning even for a moment the mask and cape of our favorite superhero.

-Steve Froehlich

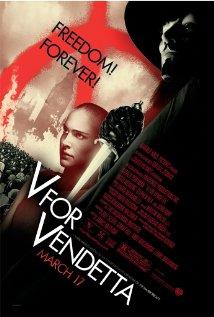

V for Vendetta

General

General Movie Review

Movie Review

Remember, remember the fifth of November, The gunpowder, treason and plot, I know of no reason why the gunpowder treason Should ever be forgot.

On the Fifth of November, 1605, Guy Fawkes, the Catholic vigilante failed in his attempt to blow up the British King and Parliament. On the Fifth of November, 2010, the man know only as “V” and masquerading as Guy Fawkes, begins his year-long campaign to overthrow the totalitarian government of Britain. To the thunderous strains of Tchaikovsky’s “1812 Overture” V conducts the overture, the pyrotechnic destruction of The Old Bailey, and the first movement of his orchestrated crusade to liberate the lives and minds of a society that has given away its freedom.

V for Vendetta is a creation of the Wachowski brothers (who brought us the Matrix triology) loosely based on the 1989 graphic novel by Alan Moore, which skewered the British government and policies led by Margaret Thatcher. Moore, however, has had his name removed from the credits of the film. The film, deftly directed by James McTeigue, resets the story in a futuristic England ruled by Chancellor Sutler (John Hurt), who ruthlessly preserves order by any means. When V, branded as a terrorist by the government, eludes capture, Sutler snarls his justification for his own brand of terrorism: “I want this country to realize that we stand on the edge of oblivion. I want everyone to remember why they need us!”

The faceless V (Hugo Weaving) offers his own vindication for his own version of vigilante vengeance, a verdict “held as a votive not in vain”: “People should not be afraid of their governments. Governments should be afraid of their people.” V enlists Evey (Natalie Portman), whose family has been victimized by Sutler’s vicious regime, in his systematic plan to overthrow the government and to “hold accountable” those who by dehumanizing him, transformed him into a super-human idea (“Ideas are bullet-proof” he informs the final evil-doer he executes, strangling him with his gloved hands).

V for Vendetta’s iconographic visuals are as bold (and obvious) as its political moralizing. Sutler preaches from his looming Big Brother-like video pulpit, and V sermonizes while he plots and executes. Unlike V, the film wears no masks as it parades before us an unflinching and impudent commentary on recent history, the current world scene, and political leadership. From one of V’s homilies: “Violence can be used for good…. A building is a symbol, as is the act of destroying it. Symbols are given power by people. A symbol, in and of itself is powerless, but with enough people behind it, blowing up a building can change the world.” Symbols are as vital to the style of the film as they are to its message, and the disturbing connection between the film’s symbols of power and still-incomprehensible horror of 911 is unmistakable.

At the center of the film, between Sutler and V each playing God, Evey struggles to find herself and discover if there is an idea or a truth, larger than herself, to which she can commit herself. Whom should she trust; what should she fear? V believes that “there are no coincidences, only the illusion of coincidence.” He means that each person must act willfully and not play the victim. On that basis he holds Sutler and all those who brutalized him responsible for their actions–they cannot excuse their actions by appealing to their good intentions or the crisis of history. He holds God similarly accountable for the way things are: “I, like God, do not play with dice and do not believe in coincidence.”

The film is a thrilling, swash-buckling, sensational political rant against an Orwellian caricature of all that’s evil in the world–of the bureaucracies of state, religion, and corporate greed; of the abuse of power eviscerating with fascist vehemence art and sexuality. But the irony is that it is no mere idea that overthrows totalitarianism and oppression–it is the actions of humans who use power for their own ends that accomplish these things.

“Is V a terrorist leader or a freedom fighter? Or merely a poor, wronged soul, out for vengeance?” (Jason Korsner, UK Screen) The brothers Wachowski do not answer that question for us. But about this they are unambiguous: we must not be passive or uninformed about the evil and injustice that is a pervasive presence in the world. Their hope is in the power of truth and ideas, and it is this hope that launches the film with Evey’s narration: “I’ve witnessed first hand the power of ideas, I’ve seen people kill in the name of them, and die defending them… but you cannot kiss an idea, cannot touch it, or hold it… ideas do not bleed, they do not feel pain, they do not love…. And it is not an idea that I miss, it is a man…. A man that made me remember the Fifth of November. A man that I will never forget.”

The faceless and impersonal relentlessness of V, in the end, cannot mask the reality that it is human to act, to believe, to hope, and to fight. V is a man, he is a human, and he loves.

-Steve Froehlich

Citizen Kane

General

General Movie Review

Movie Review

Most essays and reviews of “Citizen Kane” begin with either a haunting question or a bold statement: “Is Citizen Kane the greatest movie ever made?” or “Citizen Kane is undoubtedly the triumph of the American cinema, the greatest American film ever made!”

The origins of “Citizen Kane” are well known. In 1941, Orson Welles, the boy wonder of radio and stage, was given freedom by RKO Radio Pictures to make any picture he wished. Herman Mankiewicz, an experienced screenwriter, collaborated with him on a screenplay originally called “The American.” Its inspiration was the life of William Randolph Hearst, who had put together an empire of newspapers, radio stations, magazines and news services, and then built to himself the flamboyant monument of San Simeon, a castle furnished by rummaging the remains of nations. Hearst was Ted Turner, Rupert Murdoch and Bill Gates rolled up into an enigma.

At the center of the film’s technical brilliance is the cinematography of Gregg Toland, who on John Ford’s “The Long Voyage Home” (1940) had experimented with deep focus photography–with shots where everything was in focus, from the front to the back, so that composition and movement determined where the eye looked first.

The film opens with the death of newspaper magnate, Charles Foster Kane — he slumps over and utters a single final word, “Rosebud.” After a dizzying newsreel overview of Kane’s life and accomplishments, the story of his life is told through the eyes of those who knew him, a series of flashback remembrances. “I don’t think any word can explain a man’s life,” says one of the searchers through the warehouse of treasures which Kane left behind. Yet, the single word, “Rosebud” becomes the one word that unlocks the private world of a larger-than-life citizen. Kane’s business partner explains it this way: “All he really wanted out of life was love. That’s Charlie’s story–how he lost it.”

Roger Ebert (film critic for the Chicago Sun Times) describes the journey the story takes this way: “Citizen Kane” knows the sled is not the answer. It explains what Rosebud is, but not what Rosebud means. The film’s construction shows how our lives, after we are gone, survive only in the memories of others, and those memories butt up against the walls we erect and the roles we play. There is the Kane who made shadow figures with his fingers, and the Kane who hated the traction trust; the Kane who chose his mistress over his marriage and political career, the Kane who entertained millions, the Kane who died alone.

Now more than 60 years since it’s first release, the movie still arrests us by its stark honesty. It dares to preach to us about the human condition, that fame and power do not change what we are at the deepest part of our being, that a life glutted with success and prestige does not answer the lonely longing of a little boy lost within the faade created by media manipulation. Citizen Kane forces us to listen to the plaintive cry of every human soul, “Who will love me?

-Steve Froehlich

Crash

General

General Movie Review

Movie Review

Crash is a parable, a morality tale. As such it is terse with respect to narrative style, and it is focused with respect to theme. But the film and the subject it tackles are far from simplistic.

Paul Haggis (screenplay for Million Dollar Baby) has assembled a remarkable cast for his directorial debut. His screenplay, co-written with Bobby Moresco, gives us well-defined characters whose dialogue sounds totally believable in displaying for us the many faces of racism.

The film is like Hamlet’s play within a play—the film as a device is itself a lens, a window through which we see the world. But the view through this particular lens is of a whole society of people who have jaded attitudes toward the people all around them.

Racism. Roger Ebert comments: “All are victims of it, and all are guilty it. Sometimes, yes, they rise above it, although it is never that simple.”

How do you look at the people you pass every day, see coming toward you on the sidewalk, in the grocery store, standing on the corner? Do you think of yourself as a racist? Do you pride yourself for treating all people the same? Is it possible to live with that kind of impartiality and lack of prejudice? Officer Ryan (Matt Dillon) offers this observation, “You think you know who you are. You have no idea.”

There is a cruelty and an ordinariness to the way the characters behave. We think we recognize them sometimes by stereotype, sometimes because we see ourselves, yet each one surprises us. No one is entirely what we expect, even though each one is hauntingly familiar. Even for those characters we think we understand there is a dark twist that unsettles us and conflicts our thinking. With each new character introduced, the “hot potato” (Ken Tucker, New York Magazine) gets passed along to move the film forward. But the forward movement is not a narrative development, but a panoramic sweep that quite literally comes full circle.

The film is stylish, simple, and symbolic. Don’t be surprised by its rather shameless use of conventions. “Some critics have criticized Crash for its reliance on coincidence. Which, given it’s a deliberately structured modern parable, is a bit like damning War of the Worlds for having aliens” (Andy Jacobs, BBC).

While the film’s presentation is a bit obvious (come critics call it “preachy”) in places, it’s not a film that plays “hard-to-get.” The parable begins with a clear statement of what the film sets out to accomplish. Detective Graham Walters (Don Cheadle) narrates: “It’s the sense of touch. In any real city, you walk, you know? You brush past people, people bump into you. In L.A., nobody touches you. We’re always behind this metal and glass. I think we miss that touch so much, that we crash into each other, just so we can feel something.”

Crash has hints of redemption but does not offer substantial resolution to so great a distortion of our perspective and so deep a problem which pollutes the human condition. The film is diagnostic and descriptive, and that is a good place to begin exploring how we can live differently, how our view of people and of our relationship to all we touch can change.

-Steve Froehlich